The Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra is one of the most important historical landmarks in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, and is also known as the home of the Barra Lighthouse. This fort has a rich history linked to the defence of the city, the colonial period and navigation.

Summary of the history of the Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra

1. Origin and construction

- 16th century: Construction of the Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra began in 1534 and was one of the first forts built in Brazil soon after the arrival of the Portuguese. Initially, the fort was a rudimentary structure of rammed earth and wood, designed to defend the entrance to Todos os Santos Bay against invaders and pirates.

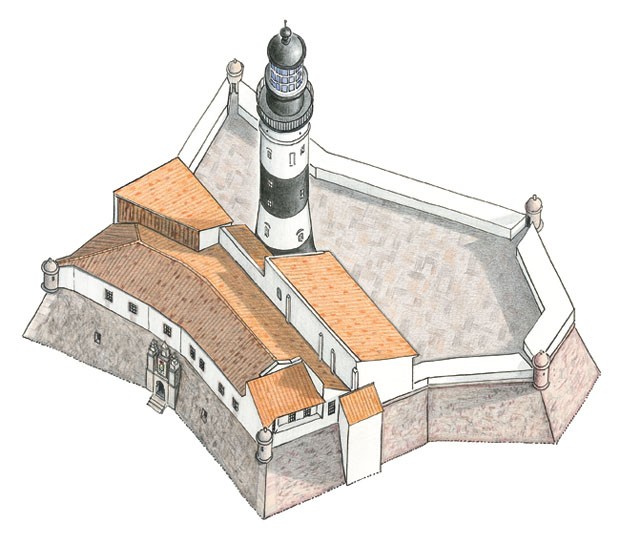

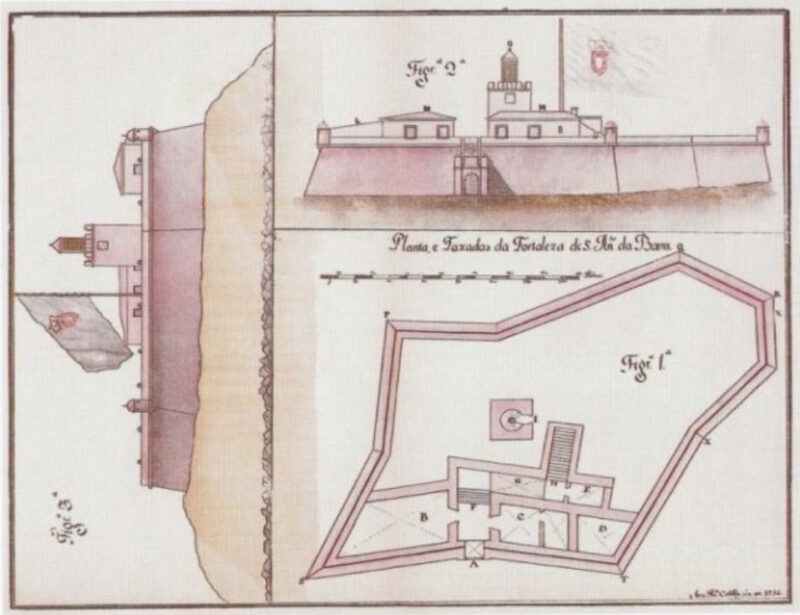

- Reconstruction in stone: Between 1583 and 1587, during the reign of Manuel Teles Barreto, the fort was rebuilt in stone, transforming it into a more robust and permanent fortress. This period of reconstruction gave the castle the approximate shape we know today, with stone walls and an irregular polygonal shape adapted to the terrain.

2. Military and strategic function

- Defending the city: The fort was designed to protect the entrance to Todos os Santos Bay, a strategic access point to the city of Salvador. Its elevated position at the tip of the peninsula on which Salvador is located provided a clear view of the sea and possible threats.

- Barra Lighthouse: In 1698, the first lighthouse in the Americas was installed at the fort, known as the Barra Lighthouse, to guide ships arriving on the Bahian coast, marking the point where they entered the bay. This lighthouse was, and still is, an important aid to maritime navigation.

3. Role in historical conflicts

- Dutch Invasions: During the Dutch invasions of the 17th century, especially in the 1620s and 1630s, the fort played a crucial role in the defence of Salvador. In 1624, when the Dutch invaded Salvador, the fort helped in the resistance, although the city fell temporarily.

- Bahian Independence: The fort was also a strategic point during the events of Bahian Independence in 1823, when Brazilian forces fought to expel the last Portuguese strongholds from Bahian territory.

4. Alterations and restorations

- 19th century: Over the centuries, the fort underwent various modifications and improvements to adapt to new military requirements and the evolution of artillery. In 1839 the lighthouse was modernised and a new cast-iron tower was installed.

- Modern Restoration: Throughout the 20th century, the fort underwent several restorations to preserve its historic structure and make it suitable for cultural and tourist use. These restorations also aimed to preserve the Barra Lighthouse, a symbol of Salvador.

5. Present status and cultural importance

- Museu Náutico da Bahia: Today, the Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra houses the Museu Náutico da Bahia, where visitors can learn about the history of navigation and explore historical artefacts related to the sea, naval history and the fort itself.

- Tourism: The Barra Lighthouse is one of the most visited tourist attractions in Salvador. From the top of the lighthouse, visitors have a breathtaking panoramic view of Todos os Santos Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, especially at sunset.

- Cultural Events: The Fort is also the venue for various cultural events, including art exhibitions, festivals and civic celebrations, consolidating its role as the centre of Salvador’s cultural life.

The Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra, with its long history and continuing function as a guide for sailors and a cultural centre, remains one of Salvador’s most important landmarks, symbolising the resistance and maritime history of the city and Brazil.

Video – History of the Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra in Salvador

História do Forte de Santo Antônio da Barra em Salvador

History of the construction of the Forte de Santo Antônio da Barra in Salvador

The Forte de Santo Antônio da Barra and Farol da Barra in Salvador is undoubtedly one of the city’s Salvador ex-libris.

However, none of the other fortifications at the head of Brazil has undergone as many metamorphoses in its more than four hundred years of existence as the Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra.

Although historians don’t usually state its exact origins, there is a very old record of the first construction of this defence in a codex in the Overseas Archives.

It transcribes a charter dated 21 May 1598, by which Brito Correia, commander of the Fort of Santo Antônio, was appointed “bastion” “begun in the bar of this city”.

This must be the version that followed the polygonal rammed-earth tower, according to the Livro Velho do Tombo do Mosteiro de São Bento.

The claim by the historian João da Silva Campos that the first fort, the octagonal tower, was the work of the government of Manoel Teles Barreto (1583-1587) is therefore acceptable.

As with the fortifications of this quarter, it is possible that Santo Antônio da Barra was born in the form of a tower, as shown by Albernaz.

These figures are probably not accidental or imaginary, as there is a graphic scale in the drawings. What’s more, the other three fortifications depicted – the redoubt of Santo Alberto, the Fort of Monserrat and the tower of São Tiago de Água de Meninos – can be confirmed by the analysis of other iconographies or, in the case of Monserrate, because it still exists.

According to the graphic scale, we can estimate the size of the axes of the regular octagon depicted at around 120 palm trees (about 26 metres).

Like the old fortress of Santo Alberto, the Água de Meninos tower and the Castelo de São Felipe, the present Nossa Senhora de Monserrate had a high entrance with a staircase and drawbridge, suggesting a typological solution of the time.

The original construction of the Santo Antônio Fort, seen from a distance, could be interpreted as a cylindrical tower, since it is an octagonal tower.

The problem is that, in this particular case, the shapes used as cartographic decoration may not be contemporary with the cartographic plan or its author, Albernaz, but correspond to older fortresses copied from other prints.

This suspicion is justified by the information contained in Diogo Moreno’s report – not only the iconography, dated 1609, but also the following reference in the description of the Monserrate fort “Stone and lime fort of the same design as that of Saint Anthony […]”.

As you can see, Moreno’s drawing doesn’t show an octagon, but a hexagon, which really resembles the Monserrate fort without the towers.

The entrance remains high and has a drawbridge, but the towers protecting access to the inner perimeter are on the outside of the curtain wall. The parapets have gunboats, albeit few.

Judging by the four pieces of artillery listed in Diogo Moreno’s Livro que dá razão do Estado do Brasil, this second version, although built of more durable stone and lime, must also have been of modest proportions.

According to a report by the military engineer José Antônio Caldas, the curtain wall of the late 17th century version had sixteen pieces of different calibres by the mid-18th century, compatible with its extended line of fire.

Some historians, in their illusions, want to ascribe some strategic value to this beautiful and photogenic fort, but they can’t be carried away by the excitement, given the coldness of the facts and the reality of the situation.

At the beginning of the 17th century, Moreno said of it that in this part “armed ships of corsairs come and go every day without the artillery that is here harming it, and even if it has colubrinas [a type of artillery piece] of sixty quintals, it will never be able to defend the bar completely”.

Later he considered it to be “an ornament of the bar”, and we all agree.

The truth is that no expert considered the fortress of Santo Antônio da Barra to be of great strategic or tactical value.

Diogo Moreno is more than clear when he says: “His Majesty has been warned many times that the forts of Santo Antônio, Itapagipe and Água de Meninos […] are of no use, both because they defend nothing and because of the great risk with which they are supported by their weakness and poor layout […]”.

Bernardo Vieira Ravasco, Secretary of State and War, also said in his report of 11 September 1660: “These three forts, almost together, are of no use to those who visit them […]”.

Even after major renovations at the end of the 17th century, which greatly increased the firepower of the Santo Antônio da Barra fort, its prestige didn’t increase.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Field Marshal Miguel Pereira da Costa was also quite emphatic about the fort’s inefficiency.

It’s worth noting that, despite its current, much more developed form, the fort was not worthy of recognition and had a stepfather, the current Gavazza hill, as a disadvantage.

The opinion about the limitations of Santo Antônio da Barra was also shared by laymen, such as friar Vicente do Salvador, who said that this fort and that of São Felipe (Monserrate) were “more for terror than for effect”.

The improvements of the new project did not solve the problem of the strategic efficiency of the fortress, because they did not help to stop the invasions of the city from the south.

It remained a defence without the capacity to harass the enemies who entered the bay. From a tactical point of view, although the range of fire had been increased, the conditions for defending its curtains were precarious.

The Batavians had taken over the fort during the invasion of 1624, so as not to leave enemy troops behind when they landed at Porto da Barra, but they didn’t invest in a large garrison to hold it. This is a fact, because soon afterwards the fort was retaken by Francisco Nunes Marinho, at the behest of Matias de Albuquerque.

In fact, it was widely believed by scholars of the capital’s defence that it would be foolish to divide the meagre troops to garrison the wilderness of Barra and Monserrate.

However, we cannot ignore the role that the fortress played as a lookout for the bar of the Bay of All Saints, a function for which it had a privileged position.

From this position, from the earliest days of Ponta do Padrão, ships coming from the north in search of its waters were signalled.

There are several documents that mention the signals with flares that travelled along the coast from the Tatuapara tower house to Ponta do Padrão, warning of approaching ships, and the shots that were fired from fortress to fortress to indicate that more than four ships were entering the Barra.

This function gave our fortress the nickname of Barra Lookout.

The lighthouse installed at the Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra, still in the 17th century, to protect sailors from the rocks and shoals of that part of the sea, shows that, in addition to its military function, which was always in doubt, it could also boast those of navigational safety and surveillance.

The lighthouse was installed at the Santo Antônio da Barra Fort in 1698, following the disaster of the Galeão Sacramento, a ship carrying General Francisco Correia da Silva, who later became governor and died in the shipwreck.

See Shipwreck of the Galeão Sacramento in Salvador BA.

To fulfil these functions, a square-based lighthouse tower was installed, which survived for a long time.

The present appearance of the fort is largely the same as it was at the end of the 17th century, except for the extension of the covered area on the embankment. The cylindrical lighthouse tower dates from the 19th century, as Vilhena depicted it as a square tower at the end of the previous century.

According to Silva Campos, the cylindrical tower is probably the result of a renovation that dates back to the imperial order of 6 July 1832, when lighting equipment bought in England was installed.

New European equipment was installed in 1890 and redesigned in 1904. The system was electrified in 1937.

See Defences of the Port of Barra – Forts of Santa Maria and São Diogo.

History of the Fort of Santo Antônio da Barra in Salvador – Salvador de Bahia Tourist Guide

Publicações Relacionadas

Solar do Unhão and the Museum of Modern Art in Salvador BA

Basílica de Nossa Senhora da Conceição da Praia: História

Rio Vermelho Neighbourhood in Salvador's Nightlife

History of the Founding of Salvador de Bahia

Church of the Third Order of St Francis History

Tourist attractions for children in Salvador de Bahia

Tourist attractions in the Gamboa neighbourhood in Salvador BA

Attractions in the Historic Center of Salvador de Bahia

Nossa Senhora dos Mares Church: Gothic Architecture

History of the Church of Nosso Senhor do Bonfim in Salvador

Fort of Nossa Senhora de Monte Serrat History

Ponta de Humaitá is one of the most charming places in Salvador

Discover the Magnificence of Nossa Senhora de Monte Serrat Fort

Discovering the Origins of the Senhor do Bonfim Ribbons

History and sights of Avenida Contorno in Salvador BA

Characteristics and History of the Church and Convent of São Francisco in Salvador

What's the best way to celebrate Carnival in Salvador de Bahia

History of the São Marcelo Fort or Forte do Mar in Salvador

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français