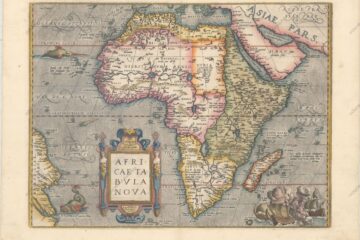

From the very beginning of the colonisation of Brazil, Portugal tried to use the experience gained in the production of sugar on the islands of Madeira and the Azores to introduce the “white gold”, as sugar was called at the time, to the vast Brazilian territories, due to its high value on the European market.

The official establishment of the sugar industry in Brazil took place after the colony was divided into hereditary captainships in 1535.

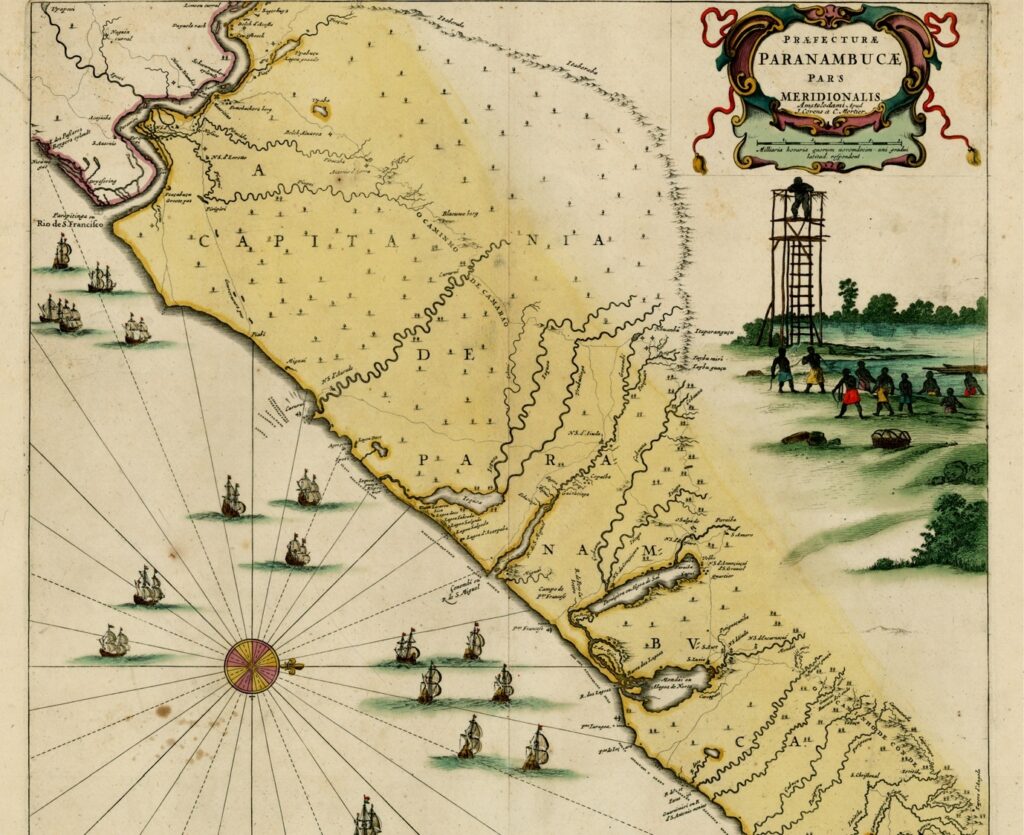

Pernambuco was the most prosperous captaincy, developing rapidly in a few years with the production of sugar, cotton and tobacco for export.

Its rapid development was due to the commitment and entrepreneurial character of its grantee, Duarte Coelho, as well as to natural factors favourable to the cultivation of sugar cane: fertile soil, regular rainfall, a hot and humid climate and a strategic geographical location, being the closest captaincy to the European market.

It was up to the grantor to pay the expenses necessary to colonise the captaincy, to contribute to the defence of the territory and to pay taxes to the Crown. In turn, the grantee was the legal and administrative authority within his captaincy and exercised the right to grant land (sesmarias) to those who had the means to establish sugar mills.

“It was private initiative that, competing for the sesmarias, was willing to come (to Brazil) to populate and militarily defend, as was the royal requirement, the many leagues of raw land that black labour would make fertile” (FREYRE, 2006, p. 80).

The settlers who received sesmarias were subject to the authority of the Crown and the grantor, but in the domains of their lands they enjoyed full authority over their family members and slaves.

In the colonial period, “[…] to be a landowner, and even a mill owner, meant much more than having a certain source of reasonable income.

It meant a title that was recognised in Brazil as a certificate of nobility” (GOMES, 2006, p. 53). (GOMES, 2006, p. 53).

The senhor de engenho was a landowner with prestige, wealth and power.

The land on which these wealthy men built their sugar mills was given to them in exchange for loyalty to the Portuguese crown, payment of taxes and military support.

As well as serving economic interests, the sugar mills played an important role in the defence and domination of Brazilian territory.

During the first two centuries of colonisation, most sugar mills were built with defensive towers, underlining their militaryimportance.

See History, biography and paintings of Frans Post in Dutch Brazil.

To cultivate his land, the sugar mill owner relied on the labour of peasants, free men without the means to build their own sugar mills, who rented small or large plots of land from the sugar mill owners to plant and harvest sugar cane.

Much of the sugar cane milled in the 16th and 17th centuries was supplied to the mills by the peasants, who initially shared in the profits but lost this privilege over the centuries.

An estate usually contains much more land than the owner can cultivate or work […]. These scraps of land become the homes of free people, of the poorer classes, who live on the meagre fruits of their labour. […]

No document is written down, but the landowner verbally authorises the inhabitant to build his little house on the land, to live in it […] and to cultivate it […] (KOSTER, 1942, p.440).

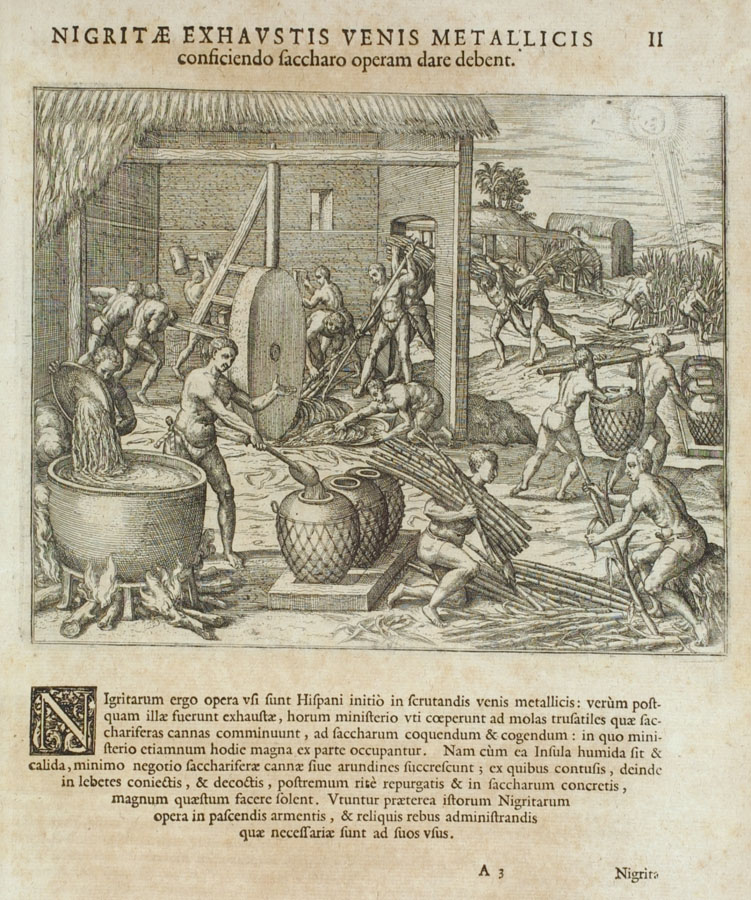

Slave labour was also widely used in sugar mills to cultivate land that was not leased, to produce sugar and to do domestic work.

In the early decades of the colonial period, sugar mill owners did not have the resources to import African slaves, so the solution to the labour shortage was to enslave Indians.

“The percentage of Indian slaves involved in sugar production decreased as the mill owners became richer and were able to import African slaves, who were less ‘lazy’ than the Indians”. (GOMES, 2006, p. 58)

Black slaves were therefore gradually introduced into the sugar industry, becoming the main labour force in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Colonial society in Brazil, especially in Pernambuco and the Recôncavo of Bahia, developed patriarchally and aristocratically in the shadow of the great sugar plantations […] (FREYRE, 2006, p. 79).

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the socio-cultural model of colonial Brazil, centred on sugar production, had the sugar mills as the basic cell of its socio-economic structure.

“And it was around and within this colonising unit that the Luso-American social identity was forged; an identity with an original character, based on mutual learning between whites, slaves, masters and captives”. (TEIXERA, s/d, p. 2).

Anyone who has had the opportunity to experience the culture of the Northeast, and especially that of Pernambuco, can still see the strong presence of values from the colonial culture, marked by the slave, elitist and patriarchal system.

Sponsorship, colonelism, prejudice against people of colour, female submission, hospitality, the mixture of spices in cooking and religious festivals are some examples of this heritage.

But in addition to the customs and traditions that are deeply rooted in the local culture, the sugar civilisation has left Pernambuco with material testimonies of exceptional historical, artistic and landscape value, of which the sugar mill is the most emblematic example.

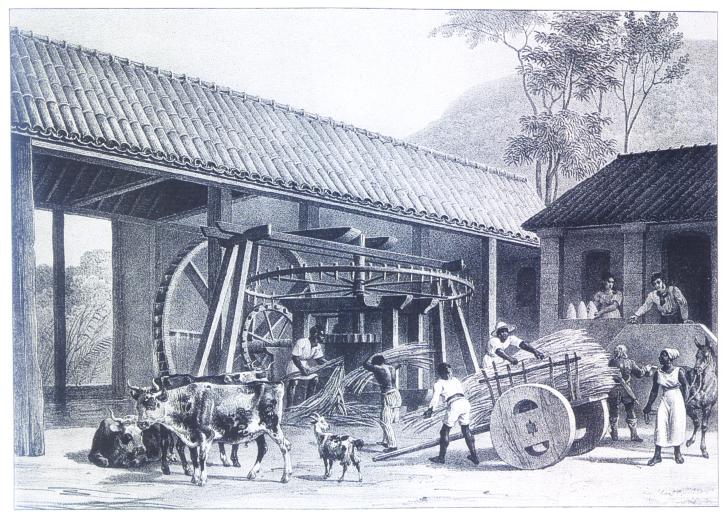

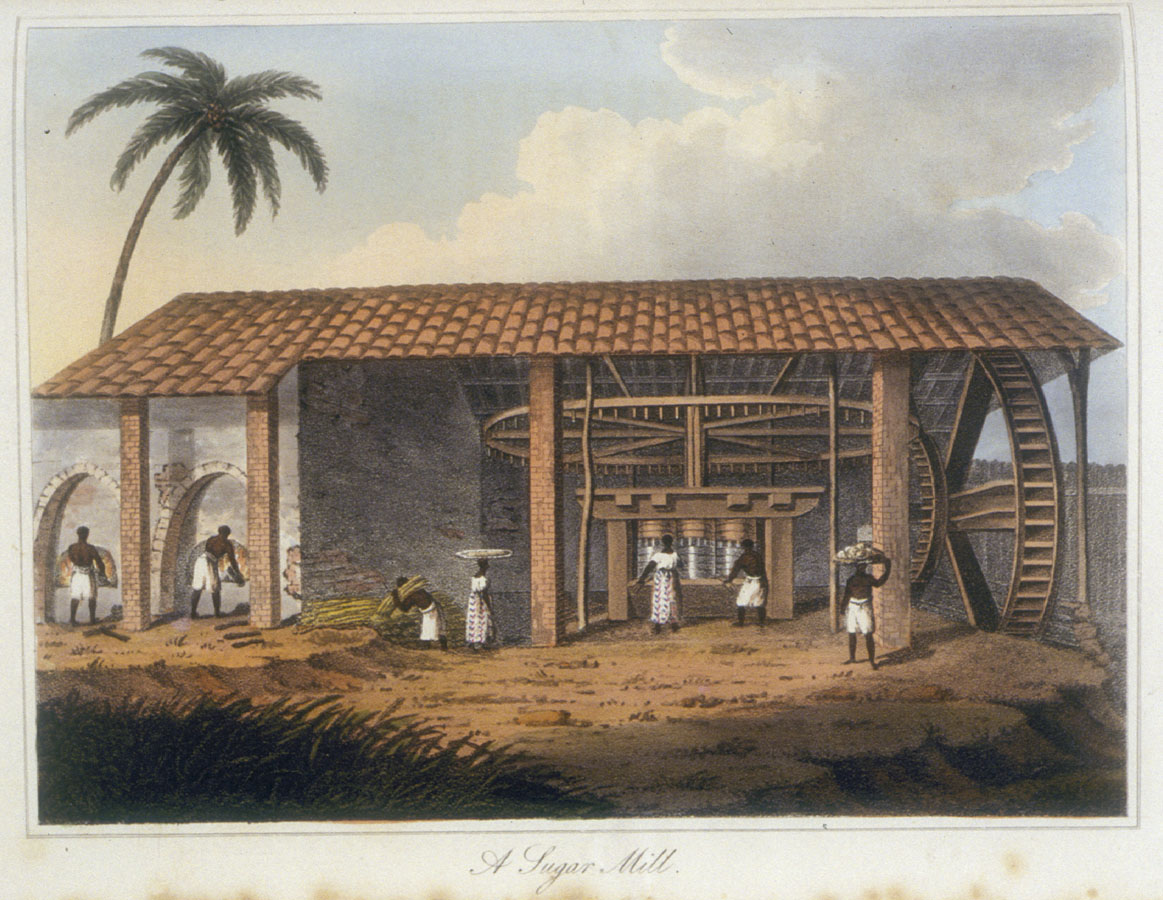

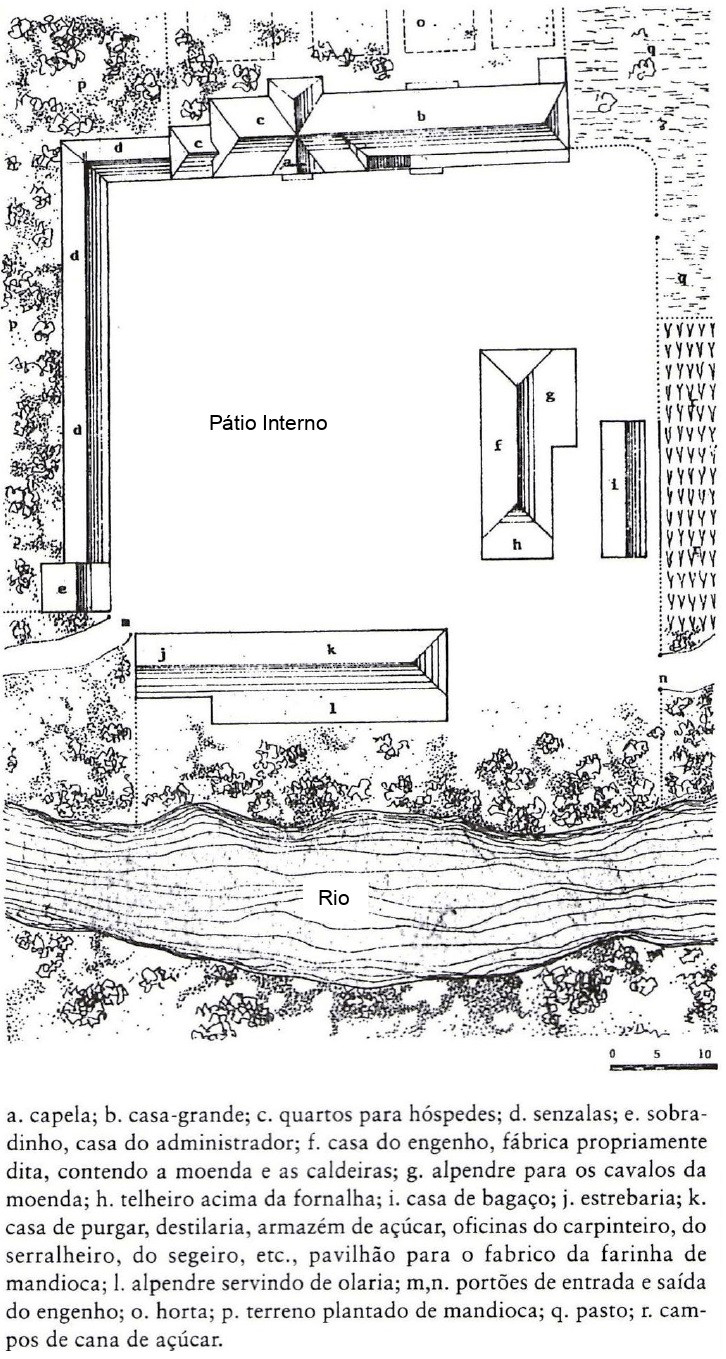

The old sugar mills consisted of: the owner’s residence, usually called the casa-grande (big house); a chapel for religious activities; a slave quarters, called the senzala (slave quarters); and a factory for the production of sugar, also called the moita (sugar mill) and the cane fields.

In most cases, they also had a vegetable garden, an orchard, a flour mill and livestock to support the inhabitants.

The sugar mill was therefore an agro-industrial unit that, although its production was oriented towards European trade, had a physical structure that minimised the need for exchanges with urban centres, leaving its inhabitants to concentrate on their socio-cultural universe.

The sugar mill was not only a production unit, but also a structuring element of the landscape and culture of Pernambuco.

The physical structure of the sugar mill […] is made up of different elements that can change according to the region and social conditions to which it belongs. Juliano CARVALHO (2005) points out that “this architectural ensemble, in its complexity, reflects a series of aspects of the society that created it: social stratification, production relations, technology, the role of religion, constituting a microcosm of its time” (FERREIRA, 2010, p. 65). (FERREIRA, 2010, p.65)

From the beginning of the sugar industry in Pernambuco, sugar mills were built mainly in the Zona da Mata region.

The fact that this region is still favoured for sugar cane plantations today is due to the following factors: its proximity to the port of Recife; the presence of several waterways in the region, which make it possible to transport the sugar production by rain and to use hydraulic energy to mill the cane; and because it is a region with medium and large trees, which were used as firewood in the mills’ furnaces.

With the continuous construction of new sugar mills throughout the 16th century, Brazilian sugar production only grew, stimulated by the Crown’s incentives and the popularisation of the product, supplying almost the entire European market.

However, in 1580, with the Spanish domination of the Portuguese crown, the tax on Brazilian sugar was increased from 10% to 20% in order to favour the marketing of sugar produced on the island of Madeira, which had already been exploited by the Spanish for several decades, but this did not stop the growth of the sugar agro-industry in Brazil.

Portugal delegated the distribution of Brazilian sugar on the European market to the Dutch, who made huge profits from this trade arrangement.

In 1605, while still under Spanish rule, Lisbon closed its port to the Dutch, who suffered huge commercial losses.

In response, the Dutch trading company, Companhia das Índias Ocidentais, attempted to occupy Bahia and, without success, sailed for the captaincy of Pernambuco.

In 1630, the Dutch took over the city of Olinda. However, the interior of the captaincy was only gradually conquered during seven years of battles, which resulted in the destruction of sugar mills and cane fields.

In 1637, Count Maurício de Nassau was sent to Pernambuco with the mission of restoring sugar production.

He did this by granting tax breaks, cancelling debts and importing slaves.

Mauricio de Nassau also spent large sums on the construction of the City of Mauritius (now the districts of Santo Antonio and São José), including exquisite buildings such as bridges, theatres and palaces.

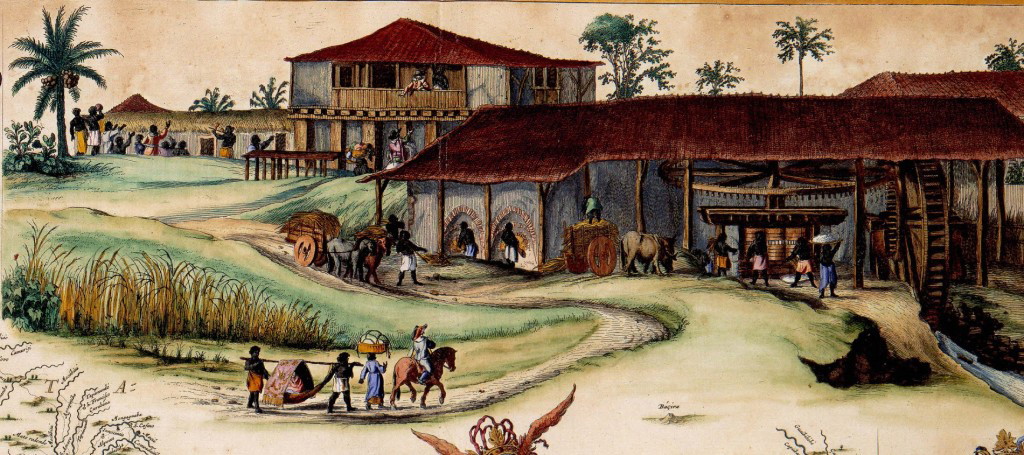

Maurício de Nassau also commissioned the Dutch painters Frans Post, Albert Eckhout and Zacharis Wagener to record the fauna, flora and architecture of the ‘exotic’ conquered land, and it is thanks to these artists that we now have a graphic record of the 17th-century landscape of Pernambuco.

From François Post‘s paintings we can deduce that in the 17th century there wasn’t a very rigid layout for the buildings that made up an engenho, but some schemes were always repeated: the casa-grande on a hillside with the façade facing the factory, the factory on a lower level and the chapel on a level equal to or higher than the casa-grande, reinforcing its symbolic importance.

There are no senzalas in these paintings, which suggests two possibilities: the slaves lived on the ground floor or in the attic of the casa-grande, or they were allowed to build huts to live in (Gomes, 1994).

Despite his many achievements, Maurício de Nassau was only able to rule Pernambuco for seven years.

Dissatisfied with the delayed financial return, the West India Company removed Maurício de Nassau from command of the Captaincy of Pernambuco in 1644.

“In the same year, the “War of Restoration” began, the aim of which was the definitive expulsion of the Dutch, which took place ten years later, in 1654″. (PIRES, 1994, p. 19).

After so many years of war, sugar production in Pernambuco was threatened by the destruction or abandonment of mills and cane fields, and by the transfer of a large number of mill owners, along with their slaves and capital, to other more peaceful and secure capitals, such as Bahia and Rio de Janeiro.

In addition to the damage caused by the Dutch occupation, there were other factors that had a negative impact on sugar production in the 17th century: a shortage of firewood to fuel the mill furnaces, competition from sugar production in the West Indies, an outbreak of smallpox, floods and prolonged droughts.

At the end of the 17th century, the Portuguese Crown, now free from Spanish domination, encouraged the development of new economic activities in Brazil that could become more profitable, such as tobacco in Bahia and mining in Minas Gerais.

This led to an increase in the cost of sugar production in Pernambuco, as financial resources and black labour were attracted to other regions of the colony.

However, “from 1750 onwards, a series of events in Europe and Brazil would reverse the chain of crises and usher in a new and brilliant period of prosperity for the Brazilian economy” (PIRES, 1994, p. 22). (PIRES, 1994, p. 22).

England and France went to war and as a result the marketing of Andean sugar, at the time the main competitor to Brazilian sugar, suffered.

In Brazil, mineral extraction declined, encouraging former miners to invest in agriculture.

In the 19th century, the occupation of Portugal by Napoleon’s troops and the transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil, which led to the opening of Brazilian ports in 1808, also had a positive influence on the commercialisation of Brazilian sugar.

In 1817, the steam engine arrived in Pernambuco, which had already been used in the West Indies to increase the speed of cane milling, bringing benefits in terms of productivity, but also increasing the cost of acquiring sugar production machinery, leading to the gradual merger of several sugar mills and the concentration of sugar production profits.

During the 19th century, new large houses were built in the countryside and exquisite townhouses in the cities to provide comfort for the sugar mill owner and his family.

He once again enjoyed the prestige, pomp and power he had enjoyed in the 16th century.

The halls of the great houses were the scene of parties, balls and banquets. It was the golden age of Pernambuco’s great and influential rural families.

The vast majority of the architectural examples of the traditional sugar mill that still exist today were built in the 19th century, with the revival of the sugar industry.

, who lived in Pernambuco between 1840 and 1846, the sugar mills of Pernambuco of this period had their buildings distributed on the land in such a way as to discontinuously delimit a rectangular interior courtyard.

We can therefore see a difference in the layout of the buildings of the mills depicted by the Dutch in the 17th century and those described by Vauthier. The latter were laid out on the land in a more rational and orderly fashion.

The typology of the buildings, their materials and construction techniques varied according to their use.

The factory was almost always built in brick with a wooden roof and ceramic tiles, and its volumetric composition, usually rectangular, was determined by functional considerations.

The nineteenth-century senzala was generally built with materials and construction techniques that were not very durable, such as pau-a-pique and adobe, which led to its rapid deterioration and consequently to the scarcity of the examples that remain today.

It was always single-storey and had a very simple layout, made up of a series of windowless cubicles, rarely more than 12m² in size, placed side by side and connected by a door to the single circulation corridor.

The chapel was the most aesthetically pleasing building in the complex, built with fine materials such as brick or masonry.

Its plan was very simple, consisting of a central nave, a high altar, a sacristy and, on the second floor, the choir.

In addition to these four basic elements, the chapel could also have a porch, side aisles, pulpit, balconies and tribunes. Its interior was richly decorated with paintings, gilding, carved wood, sacred images, chandeliers, etc.

“However, this decoration should not be understood as ostentation on the part of the mill owners. It should be remembered that social life in the countryside was limited to religious services and festivals”. (PIRES, 1994, p. 37).

The casa-grande could be sumptuous, built with fine materials, or modest, using less durable materials, depending on the proximity of the engenho to the city. If it was close to a town centre, the casa-grande was only used to house the Engenho Lord during the milling season.

For the rest of the year, he and his family lived in town. However, when the engenho was far from the city, the casagrande took on the appearance of a palace and was the main, or only, residence of the engenho owner and his family.

According to architect Geraldo Gomes, the large houses built in the 19th century can be categorised into three types: bungalow, neoclassical sobrado and chalet.

The bungalow is a medium-sized, single-storey building that may have a semi-underground cellar, a hipped roof and its main feature is the U-shaped porch that accompanies three of the building’s façades.

The neoclassical sobrado is a large two-storey building with a rectangular floor plan and a gabled roof.

The medium-sized chalet is similar to the bungalow, except that it has a gabled roof with a ridge perpendicular to the main façade and may have some eclectic ornamentation, as it only appeared in rural areas at the end of the 19th century.

During this period, the sugar industry experienced a new decline due to the following factors: competition from beet sugar, which was beginning to be produced in Europe; the beginning of a new economic cycle focused on coffee production; the abolition of slavery in 1888; the beginning of the country’s industrialisation; and the fall in the price of cane sugar on the international market.

In 1884, with the aim of modernising sugar production in Pernambuco, the imperial government established four central mills in the province.

These were larger than the traditional mills and had modern steam-powered machinery capable of producing crystal sugar.

The central mills were able to produce a greater quantity of sugar at a lower cost, but they didn’t grow the sugar cane that they crushed.

This was still supplied by the “banguês” (traditional mills).

From the point of view of spatial and landscape organisation, the Engenho Central was the first – and fatal – step in the disintegration of the sugar universe.

With the transfer of industrial activity (and a significant part of the profits) to industry, not only did the mills lose their raison d’être, but each production unit was weakened.

If previously the existence of a micro-village for each mill was indispensable, given the large number of tasks to be carried out, now the factories, and with them the potteries, could be dismantled; there was no longer a need for specialised labour; the owner needed to spend less time in the countryside, and with him, his family, so that the construction of the casa-grande became more symbolic than useful; and the decline in population even reduced the importance of the chapel. (CARVALHO, 2009, p. 37).

A few years after the creation of the Central Sugar Mills, the mills were created on the initiative of private individuals. As well as concentrating sugar production and using industrial techniques, they also took over the planting and harvesting of sugar cane, adding the land of former mills to their estates or, in some cases, transforming the mills into mere suppliers of raw materials. The mills gradually replaced the central mills, partly due to the irregular supply of cane for milling.

The mill owners preferred to produce brandy, rapadura or even sugar using the old methods rather than supplying the central mills with cane.

Overall, the First Republic in the northeast (1889-1930) can be characterised as a period of transition, marked by the gradual replacement of mills by processing plants.

In other words, this period saw the gradual decline of the old sugar cane aristocracy in the northeast and the emergence of new sectors or social groups based on the development of industrial and financial capital (PERRUCI, 1978, p. 105).

However, I understand the installation of the central mills and later the sugar mills as a process of modification of the sugar universe, not its destruction.

Culture is constantly changing, as is everything that is closely linked to it, and to deny the changes that the cultural landscape has undergone would be to deny its very nature.

However, these changes have resulted in the abandonment of old mill buildings and cultural practices (such as religious festivals, songs and dances), changes in the division of rural land and changes in rural labour relations, from an informal relationship of rent and housing to a temporary contract of wage labour.

This change in rural labour relations, which began in the 1940s, reflects the capitalist and industrial principles of rural production, where workers lose ownership of the means of production and are left with only their labour power.

Small farmers and rural workers were expelled from the countryside, returning only during the sugar cane harvest, and became known as bóias-frias.

These changes had repercussions in both rural and urban areas: the rural exodus; the acquisition of land for sugar cane plantations, previously occupied by houses and gardens; insecurity for rural workers, who no longer had stable employment; the emergence of the landless movement.

Throughout the 20th century, the process of displacing small farmers from the countryside and concentrating sugar production in ever larger factories continued at the same rate as sugar production in the north-east.

In 1975, this process was accelerated by the Pro-Alcohol or National Alcohol Programme, which was set up in response to the sharp rise in the price of a barrel of oil in 1973 and 1979 to stimulate the production and consumption of alcohol as a substitute for petrol.

To this end, the government encouraged the expansion of sugar cane plantations, the modernisation and expansion of existing distilleries and the installation of new production and storage units, as well as providing subsidies to mill owners to produce alcohol instead of sugar.

“The stages in the production of sugar and alcohol differ only from the moment when the juice is obtained, which can be fermented to produce alcohol or processed to produce sugar”.

Proálcool

It is up to the sugar miller to consider which of the two products derived from sugar cane offers the greatest economic advantage, based on international trade prices and government incentives.

At the time Pro-Alcohol was introduced, the price of sugar on the market was low, making it easier for mills to switch to alcohol production.

Brazil’s fleet of gasoline-powered cars was quickly replaced by alcohol-powered cars; alcohol production in the country peaked at 12.3 billion litres between 1986 and 1987.

Since 1986, however, the price of a barrel of oil has fallen significantly and remained stable, making ethanol an uneconomical fuel for both consumers and producers.

In addition to this factor, the price of sugar on the international market rose significantly during the same period, leading mill owners to prioritise sugar production.

Another factor that greatly contributed to the weakening of Pro-Alcohol was the supply crisis that the country experienced during the 1989-90 off-season, which discredited the programme in the eyes of car manufacturers and consumers.

Although short-lived, the crisis, together with a reduction in government incentives for the use of ethanol, led to a significant drop in demand and consequently in sales of ethanol-powered cars in the following years, to the point where car manufacturers stopped selling new ethanol-powered models

.

Today, however, alcohol production has been given a new lease of life by the technology of flex-fuel engines, which can run on alcohol, petrol or any mixture of the two.

This technology was developed in the United States and introduced in Brazil in 2003, with rapid market acceptance.

Today, almost all car models are offered by car manufacturers with flex-fuel technology.

Unlike thirty-five years ago, when Pro-Alcohol was created, it is a private initiative that is currently investing in the construction of new factories and the expansion of sugar cane plantations, based on growing demand from the consumer market and encouraging estimates that point to an additional demand of 10 billion litres of alcohol and 7 million tonnes of sugar in 2010 (according to a study by Única).

“The prospects of increased alcohol consumption add up to a favourable time for increased sugar exports, and the result is the beginning of an unprecedented wave of growth for the sugar and alcohol sector.” (PRÓÁLCOOL).

Eight decades after the establishment of sugar mills in Pernambuco, the profile of the State’s sugar industry has changed considerably.

The modernisation of sugar production in the state has made it possible to maintain this economic activity, but has contributed significantly to the degradation of the material heritage associated with the sugar civilisation.

Only a few of Bangkok’s sugar mills remain. Most were demolished by the mills to make way for sugar cane plantations, or simply abandoned and left to deteriorate over time.

The change in the socio-economic structure transformed the mills into farms: from sugar producers, they became suppliers of cane to the mills.

With the consequent disappearance of the “lord of the mill” and the emergence of the administrator, changes were made to the mill buildings.

The change in use inevitably led to other changes. The Engenho is no longer an agro-industrial centre, and the loss of the importance that this condition gave it contributed decisively to its abandonment by the former owners.

The large house is uninhabited or, in some cases, occupied by residents who contribute to its disfigurement.

For the same reasons, the chapel, when it exists, no longer functions as a religious temple and the “moita” […] has become a stable or storage space.

Rare are the large houses that are still well preserved. Very few moitas still have their typical machinery. In addition to the change in use, lack of interest, partly due to misinformation about the value of these historic sites, and the financial difficulties of the current owners are responsible for the decadent appearance of most of the mills.

Not to mention the large number of mills that have been absorbed by other mills, transformed into distilleries, divided into small properties and/or simply no longer exist. (PERNAMBUCO, 1982, p.10).

History of the Pernambuco Sugar Mills – Beginning and End

Publicações Relacionadas

Portuguese Empire in Brazil - Portuguese Royal Family in Brazil

Pre-colonial Brazil - The forgotten years

Portuguese maritime expansion and the conquest of Brazil

Dutch Invasion of Salvador in 1624: Overview

The History of the Jews in Colonial Brazil

Transfer of the Portuguese court to colonial Brazil

Monoculture, Slave Labour and Latifundia in Colonial Brazil

Installation of the General Government in Brazil and foundation of Salvador

Transition between colonial and imperial Brazil

Shipwreck of the Galeão Sacramento in Salvador: Learn the story

Independence of Brazil - breaking of colonial ties in Brazil

The Origin of Sugarcane and Sugar Mills in Colonial Brazil

Establishment of the Portuguese colony in Brazil

Carlos Julião: The Military Engineer and Draughtsman Who Portrayed Colonial Brazil

The occupation of the African coast and Vasco da Gama's expedition

Learn about the periods of Brazil's colonial history

The history of sugar cane in the colonisation of Brazil

Pedro Álvares Cabral's expedition and the conquest of Brazil

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français