The representation of Brazil through European eyes in the 17th century

From the 16th century, conquerors began to interpret South America not only through words, but also through images. This process of visual representation gained momentum with the Dutch invasion of northeastern Brazil between 1630 and 1654, when European artists with solid technical training – still influenced by the medieval guild – began to draw the American tropics on the spot.

The city of Recife became the main centre of the Dutch occupation, after unsuccessful attempts to conquer the seat of the Portuguese administration in Bahia. The invaders then decided to settle directly in the Captaincy of Pernambuco, a strategic region due to its sugar production, considered the main source of wealth in colonial Brazil.

In the early years, the conquest required intensive military action and the main objective was to expand the area under the control of the Western Indian Company (WIC).

From 1637, however, this scenario changed with the arrival in Brazil of Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, who brought with him an entourage of cartographers, painters, engravers, doctors, botanists and other specialists to mapping and documenting the New World. The aim was twofold: to demonstrate the economic viability of the occupation to Dutch investors and, in keeping with the ideals of the time, to bring civilisation to a still little-known land.

The presence of Nassau’s entourage in Brazil was a unique phenomenon in the American context of the 17th century. Artists and scientists travelled the muddy and precarious streets of a distant tropical port at the behest of an illustrious nobleman eager to demonstrate the colony’s potential and justify the risks of the venture.

This experience produced a huge amount of cartographic, pictorial and scientific work. The resulting material became the first coherent body of geographical, botanical, zoological and ethnographic information on the Americas, which managed to gain a certain credibility within the European scientific community, even though it was driven by commercial interests.

Among the members of the mission were names such as Frans Jansz Post, Albert Eckhout and the physician and naturalist Willem Piso, who arrived in Brazil in 1637, as well as the cartographer Zacharias Wagener. In 1638 they were joined by the naturalist George Marcgraf. Military personnel associated with the WIC also contributed to the records and studies encouraged during Nassau’s reign.

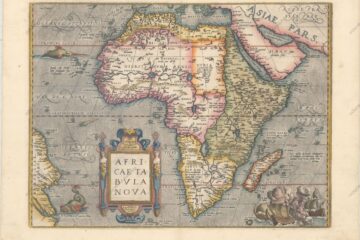

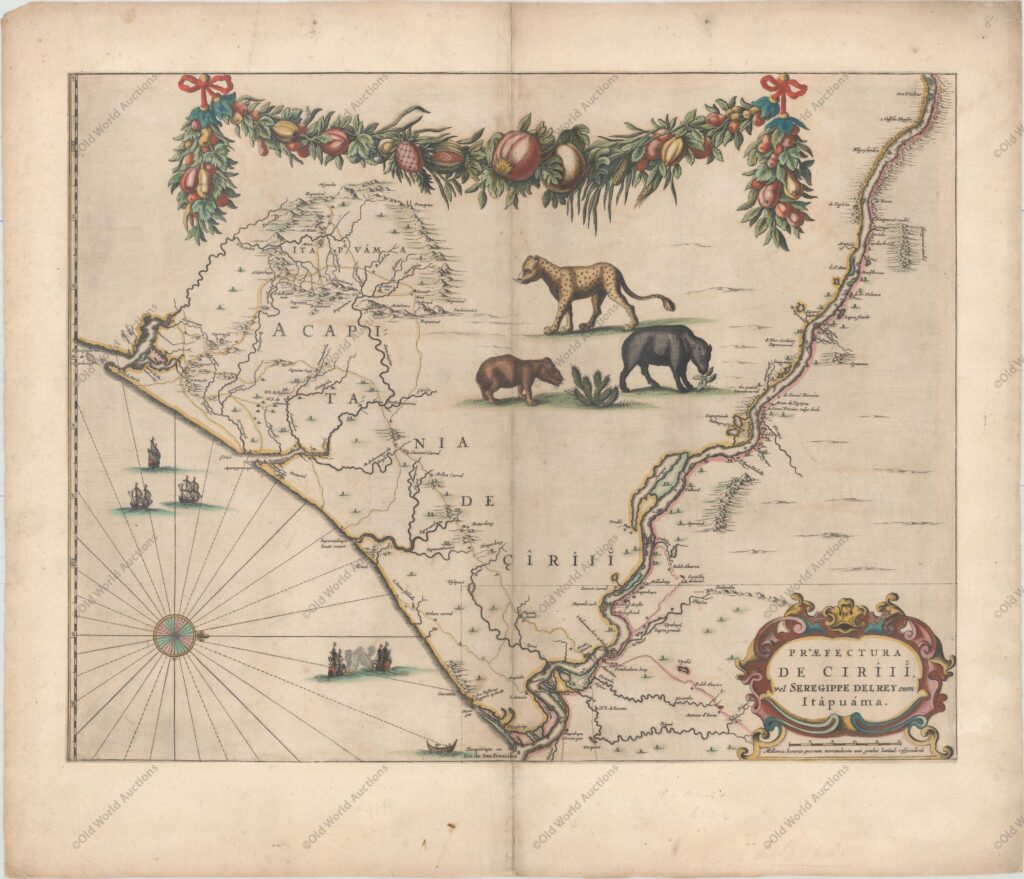

The artistic and scientific output of this team was diverse and subject to multiple interpretations. Albert Eckhout, for example, is recognised as the first European painter to take an ethnographic view of the native peoples of the Americas. The maps produced by Marcgraf, Wagener and others such as Claes Visscher, Hessel Gerritz and Izaak Commelyn show the main urban centres on the north-eastern coast and their defensive structure of fortresses, castles and artillery batteries. These maps also highlight the sugar-producing regions and the rivers and natural harbours, which were essential for the transportation of production and the economic control of the WIC.

A landmark of scientific production at that time was the treatise Historiae Naturalis Brasiliae by Piso and Marcgraf, published in 1648 under the patronage of Nassau. The work, rich in illustrations of the fauna and flora of the Brazilian northeast, is considered one of the most important scientific contributions to the knowledge of the nature of the New World and remained the only illustrated work on the natural history of Brazil until the 19th century.

With the return of Nassau and his entourage to the Netherlands in 1644, several historical treatises were written about his work in Brazil. Of these, Caspar Barlaeus’ stands out, written at the request of Nassau himself, with engravings inspired by the paintings of Frans Post.

During the seven years of Nassau’s presence in Brazil, a hungry market for images and accounts of the New World was consolidated in Europe – especially among the Dutch, nobility and bourgeoisie. This demand, which continued throughout the 17th century, ensured Frans Post‘s artistic and financial livelihood until his death in 1680 in Haarlem.

Frans Post’s biography

Frans Post (ca. 1612-1680)

Frans Post was a Dutch painter born in Haarlem around 1612, the son of Jan Jaszoon Post, a stained-glass painter. He is recognised as the first European artist to systematically portray Brazil and one of the great masters of 17th-century landscape painting, although his full recognition came centuries after his death.

Journey to Brazil

Post arrived in Brazil in 1637 as part of the entourage of Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, then Governor-General of the Dutch colony in the northeast, and stayed until 1644.

He was probably introduced to Nassau by his brother, Pieter Jasz Post, an architect and painter. In Brazil, at the age of 25, he was deeply influenced by the tropical light and exotic subjects he encountered, which contrasted sharply with the Dutch landscapes.

Influences and style

Influenced by artists such as Cornelis Vroom, Pieter Molijn and Salomon van Ruysdael, Post incorporated the tradition of the idyllic Dutch landscape into his Brazilian paintings.

His early work in Brazil, which was documentary and very realistic, evolved over time, becoming more stylised and idealised to suit European tastes, especially those of his patrons.

His paintings are characterised by wide skies, low horizon lines, meticulously painted vegetation in the foreground and diffused atmospheric light. A notable technique of Post’s was the use of chiaroscuro: the contrast between the light of white clothing and the darkness of black figures – often enslaved people carrying goods – created dramatic and symbolic visual effects.

European recognition and legacy

While in Brazil, he produced at least 18 paintings, which returned to Europe with Nassau and were exhibited in 1679 at the Court of Louis XIV in Versailles. Some of these works are now in the Louvre Museum. Curiously, on at least one of them, the artist signed “F. Correio”, a playful translation of his surname, which may have made it difficult to identify him later.

Return to the Netherlands

Back in the Netherlands in 1644, Frans Post continued to paint tropical scenes based on the sketchbooks he had made in Brazil. These works became more fanciful: he rearranged real elements in an idealised way, creating landscapes that, although exotic, no longer corresponded exactly to Brazilian reality. It was a process similar to that of the painters of the Bamboccianti school, who portrayed Italian scenes from a foreign perspective.

Maturity and thematic repetition

Between 1644 and 1659, there was still a certain topographical rigour in his work. After this period, however, Post began to populate his compositions with exotic animals – armadillos, snakes, lizards and even scenes of beasts of prey – and to use more intense colours. In the 1660s he reached his artistic maturity: his paintings became denser, composed of chromatic layers in shades of green and blue, harking back to the Flemish tradition. It was the height of his commercial career when he began to repeat established themes such as sugar mills, colonial houses and views of Olinda.

Decline and death

Despite his success, his last years were marked by decadence. Suffering from alcoholism, his output lost momentum. Yet his prestige endured: his friend and fellow great painter, Frans Hals, painted his portrait around 1655, immortalising him in the artistic memory of the Netherlands.

Frans Post died in 1680, probably at the age of 68. His legacy, however, survives as the first great visual chronicler of colonial Brazil, capable of balancing documentary rigour and artistic fantasy, building a bridge between two worlds through painting.

Portrait of Johan Maurits (1604-79), Count of Nassau-Siegen and Governor of Brazil (1670 – 1680)

Michiel Van Musscher (Dutch, 1645-1705)

Paintings and works by Frans Post

History, biography and paintings of Frans Post in Dutch Brazil

Publicações Relacionadas

Diógenes Rebouças and His Architectural Legacy

The 7 north-eastern rhythms and musical styles that enchant Brazil

The French artistic mission and the legacy of Jean-Baptiste Debret

The culture of Northeastern Brazil: how it originated, influenced and flourished

Candomblé in Bahia, Origin and Religiosity of the Bahian People

Discover the Magic of Iemanjá Festival in Salvador de Bahia

June festivals: Tradition and Culture in the Northeast of Brazil

Exploring Capoeira in Salvador: A Martial Art Rich in History

Brazil's historic moments illustrated in great works

Northeastern architecture marked by typical features of colonial structures

Monte Pascoal National Park: Pataxó culture and Brazilian history

European architecture - chronology, styles and characteristics

History of Baroque Architecture in the Northeast and Minas Gerais

The rhythm of Candomblé in Bahia

Turban is Religion, Fashion and Culture in Brazil and the World

The Baianas' costume is influenced by African culture

Brazil's northeastern subsoil has emeralds and archaeology

Bahia joins the ethnic tourism route

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français