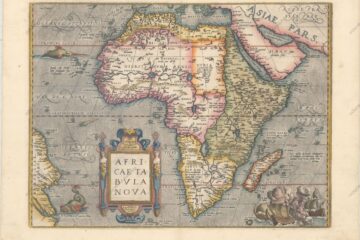

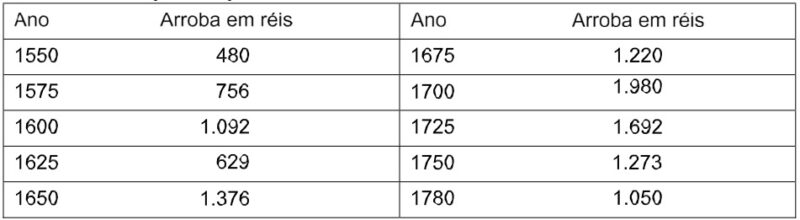

Colonial sugar mills in Brazil

1 Introduction

In this chapter we will study the establishment of the so-called colonial sugar mills in Brazil.

The sugar mills established by the Portuguese, mainly in the Northeast and in the region of São Vicente, were to become a lucrative industry responsible for the production of sugar, which was widely used as a culinary product in Europe.

To reflect on the importance of engenho in Brazil’s colonial history, we will use the book “Casa Grande e Senzala” by the Pernambuco historian Gilberto Freire. This book is a landmark in the cultural historiography of Brazil and the world, as the author reflects on Brazilian history through the lens of race relations.

Another important aspect of this theme is the religiousness of the colony.

The Catholic religion introduced by the Portuguese was strongly influenced not only by indigenous religions, but above all by African religions. In many regions of Brazil, there was a real syncretism that mixed the three religious expressions into one.

Syncretism – The word syncretism means mixture! In Brazil, syncretism did not only exist in the religious aspect, but in many other forms of expression of the different peoples that contributed to the formation of the Brazilian people.

2. Sugar mills

With the intensification of colonisation that took place after the establishment of the General Government in 1549, several colonial sugar mills were established in Brazil.

O CICLO DO AÇÚCAR - Sociedade e Economia Colonial

Despite this, Martim Afonso de Souza had already established sugar mills by 1530, and the first sugar mill was built in the region of São Vicente, in what is now the state of São Paulo.

Sugar cane was introduced to Brazil by Martim Afonso de Souza, also the owner of the first sugar mill built in the country, in collaboration with the Dutchman Johann Van Hielst (known as João Vaniste), representing the Schetz, wealthy shipowners, merchants and bankers from Amsterdam (BUENO, 2003, p. 44).

According to Mary Del Priore and Renato Venâncio (2006), sugarcane was part of the colonial economy from the very beginning of colonisation.

There is evidence that sugar cane arrived in Brazil in the early years of colonisation, between 1502 and 1503.

Its systematic exploitation, however, took another decade.

In 1516, the powerful House of India, the metropolitan body in charge of customs, was looking for sugar masters to work in the mills that were to be built near the coastal factories. By 1518, slaves from Guinea and settlers from Madeira were already at work.

From 1520, the customs house in Lisbon began to collect duties on sugar from the land of Santa Cruz. When the Portuguese first arrived in Brazil in the 1500s, they called the country “Terra de Vera Cruz”.

Although sugar cane had been grown in Brazil since the early days of colonisation, it was not until 1530 that it became an economically viable product, thanks to the initiatives of Martim Afonso de Sousa.

It’s important to note that even in the early days of Brazil’s colonisation, there was an agreement between Portugal and the Netherlands regarding the production and marketing of this valuable product.

This partnership was threatened by the Iberian Union of 1580, when Portugal and Spain were ruled by the same king (King Felipe II).

This union led to serious conflicts with Holland, as the Spanish were enemies of the Dutch and prevented them from maintaining trade relations with Brazil.

This led to the Dutch invasion of north-eastern Brazil.

As colonisation intensified, the Portuguese, in partnership with the Dutch, began to invest large sums of capital in the construction of sugar mills and the consequent planting of large areas of sugar cane.

According to Eduardo Bueno (2003, pp. 44-45):

With the arrival of the donatários, the sugar culture in Brazil gained tremendous momentum.

Barred by law from exploiting brazilwood (a crown monopoly), the donatários, led by Duarte Coelho, brought in settlers from the island of Madeira, began to clear the coastal forests and set up their first mills.

The increase in population in Europe, the relative fall in the price of the product, the fertility of the northeastern Massapé, all contributed to sugar becoming a product that was increasingly consumed in the cities and fought over on the market.

It must be said that the Portuguese were innovative colonists for their time, as Gilberto Freyre points out in his book Casa Grande e Senzala:

The Portuguese coloniser of Brazil was the first of the modern colonisers to shift the basis of tropical colonisation from the mere extraction of mineral, vegetable or animal wealth – gold, silver, timber, amber – to the creation of local wealth.

Although the wealth they created – under the pressure of American conditions – was at the expense of slave labour: touched, therefore, by that perversion of the economic instinct which soon led the Portuguese from the activity of producing values to that of exploiting, transporting or acquiring them (2003, p. 79).

Still quoting Freyre:

Colonial society in Brazil, especially in Pernambuco and the Recôncavo of Bahia, developed patriarchally and aristocratically in the shadow of the great sugar plantations, not in random and stable groups; in large houses of rammed earth or stone and lime, not in adventurers’ huts.

Oliveira Martins notes that the colonial population in Brazil, “especially in the north, was aristocratic, that is to say, the houses of Portugal sent branches overseas; from the beginning of the colony it presented a different aspect from the turbulent immigration of the Castilians in Central and Western America”.

And before him, Southey had already written that in the plantation houses of Pernambuco, during the first centuries of colonisation, one could find the decency and comfort that would be sought in vain among the populations of Paraguay and the Plata (2003, p. 79).

Everything conspired to make Brazil the world’s largest producer of sugar.

To give you an idea, in 1628 there were already around 235 sugar mills in Brazil, the vast majority in the north-east.

When the Dutch invaded in 1637, production in Pernambuco, Itamaracá, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte exceeded 1 million arrobas per year (BUENO, 2003).

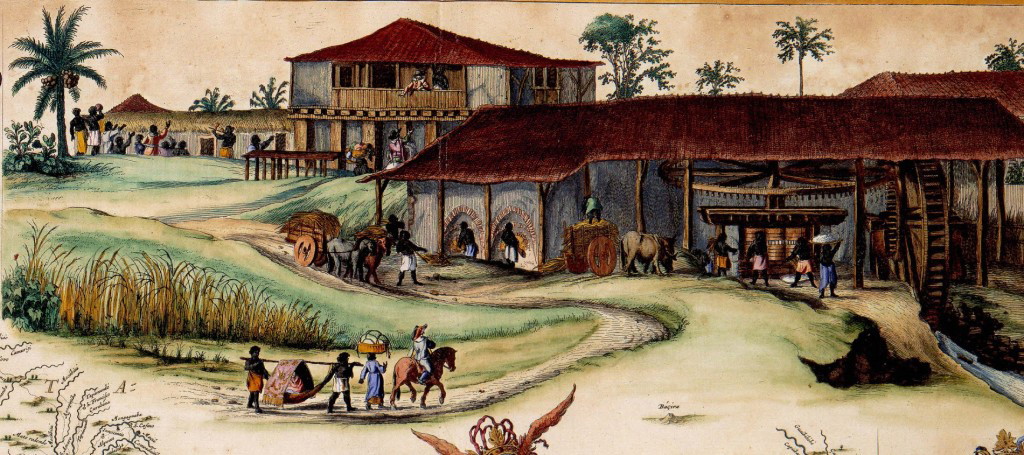

It must be emphasised that there were different types of sugar mills, depending on the purchasing power of their owners, from small manual sugar mills, as in the picture above, to large hydraulic mills. Despite the differences, they all produced sugar and sugar cane by-products.

Despite the large number of sugar mills, it is important to note that the real profit from this activity came from the distribution and reign of sugar in Europe, an activity generally carried out by the Dutch, and not necessarily from the planting of sugar cane and the production of raw sugar in the mills.

Again quoting Eduardo Bueno (2003, p. 45):

But the vitality and great profitability of the sugarcane plantation seem to have passed only through the great house that housed the Engenho lords. O

The real profits went to those who shipped the sugar to Europe. These profits were used to make new loans to the sugar mill owners, who thus lived in “perpetual debt, from which they periodically asked for forgiveness”.

In any case, after one or two good harvests, many owners sold everything they had and returned to Portugal.

It is true that many of the Portuguese colonists who chose Brazil as their capital investment did not bring their families with them.

In this sense, the Engenho became a veritable Babylon, as the Portuguese would soon cross their bodies with black and Indian women, thus encouraging the beginning of miscegenation.

According to Father Antônio Vieira (apud BUENO, 2003, p. 48):

Whoever sees, in the darkness of the night, those enormous furnaces that burn incessantly […] the noise of the wheels, of the chains, of the people, all coloured the same night, and all groaning, without pause or rest; whoever sees all the confusing and thundering machinery and apparatus of that Babylon, cannot doubt, even if he has seen Etnas and Vesuvios, that it is a likeness of hell.

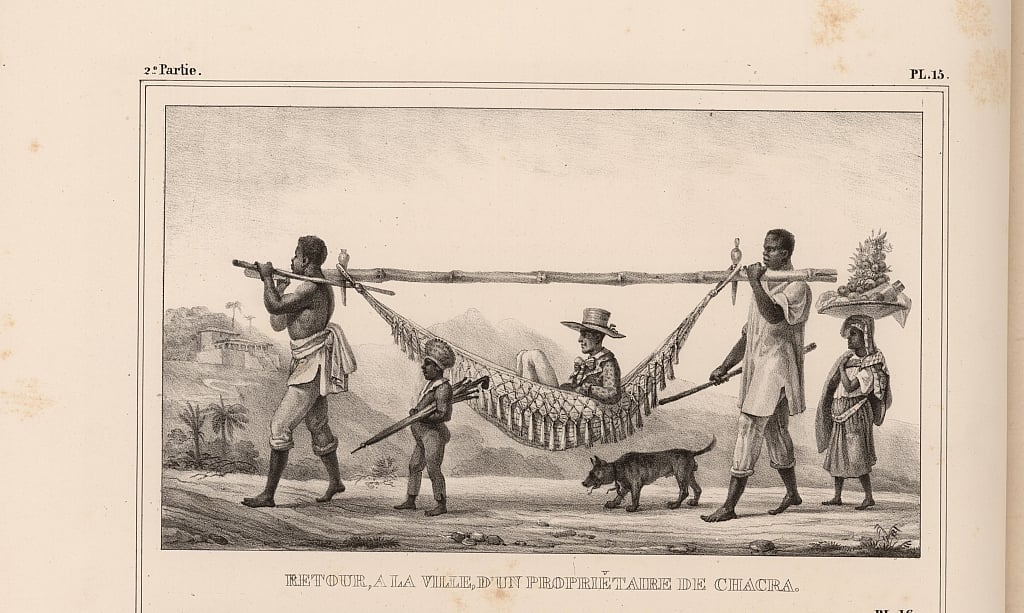

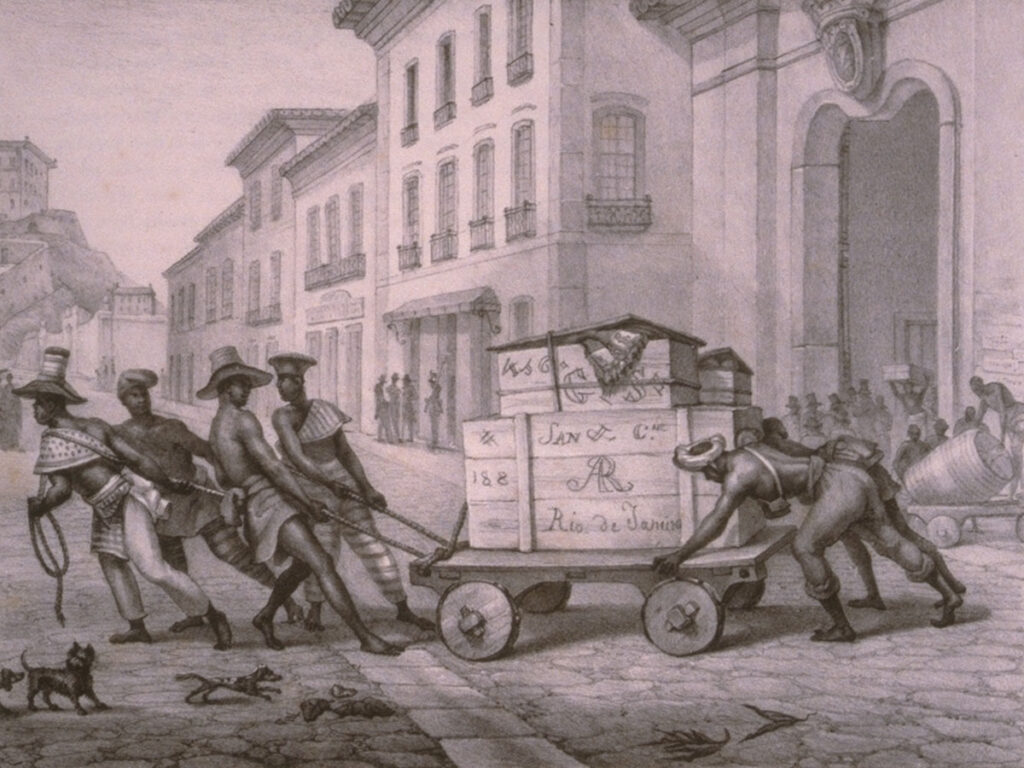

The words of the famous Jesuit priest reinforce the idea that the slave was a social subject that did everything.

The words of this famous Jesuit priest reinforce the idea that the slave was the social subject who did everything in the colony.

The importance of the sugar mill cannot be underestimated, since the most profitable activities were those of the kingdom and the distribution of sugar in Europe.

In fact, the importance of the Engenho was not only economic, but also social and cultural.

In the next section, we will examine the social and cultural importance of the colonial sugar mill.

3. Social and cultural significance of the colonial sugar mill

The Portuguese colonists in Brazil invented a structure called the colonial sugar mill.

It was a complex made up of various outbuildings, from the chapel to the purge house, the boiler house, the flour house, the bagasse house, the mill wheel, the corral, the orchard, the cemetery and the slave quarters, often next to the main house.

These were typically Lusitanian buildings, with all the symbolism they might have had in Portugal, but the people who lived in them were from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds.

According to Gilberto Freire (2003, p. 79)

The Portuguese coloniser of Brazil was the first of the modern colonisers to shift the basis of tropical colonisation from the extraction of mineral, vegetable or animal wealth – gold, silver, timber, amber, ivory – to the creation of local wealth.

This wealth – created by them under the pressure of American conditions – was created at the cost of slave labour: it was therefore affected by that perversion of the economic instinct that soon led the Portuguese away from the activity of producing values to that of exploiting, transporting or acquiring them.

The Engenho was very important because it was a landmark of civilisation in the middle of the forest, and it was here that Afro-Brazilian culture developed. In this structure, whites and blacks lived together in a relationship of master and slave.

According to Gilberto Freire (2001, p. 27)

No culture, no people, no people after the Portuguese, has had a greater influence on the Brazilian than the Negro.

Almost every Brazilian bears the mark of this influence. From the black woman who rocked him and fed him.

From the sinhama (wet nurse) who fed him, making the ball of food herself with her fingers.

We must realise that the success of the sugar mill in Brazil was due to the cultural characteristics of the African, who was very different from the Indian.

The blacks imported from Africa – as has already been said – generally had a superior culture to the Indians.

They were also better adapted to the tropics. Unlike the Indian or the caboclo, who were discouraged by the rigours of the sun.

In modern terms, the black man was an extrovert (cheerful, easy, funny, accommodating, self-confident) and the Indian an introvert (sad, difficult, bison-like, reluctant) (FREIRE, 2001, p. 27).

These characteristics explain why the black man was the white man’s greatest ally in the colonisation of Brazil.

Despite this, black people were brought to Brazil from all over Africa. In the words of Gilberto Freire (2001, p. 29)

The Angolas were Bantu; like the Congo, they were good at rough work.

The “tricky” Angolas were good at starting the “boçais” on the eito (clearing a plantation with a hoe or hand tools).

The Ardas came from Dahomey. They were “so fiery that they wanted to cut everything with one blow”, as Henrique Dias said of them.

The Minas (Nagô) of the Gold Coast. Dahomey and the Gold Coast were the centres of Sudanese culture.

The black Sudanese are among the tallest people in the world. In Senegal, they even look like they’re walking on stilts; with their shirts on, they look like souls from another world.

The blacks from Guinea, beautiful in body, were excellent for domestic work, especially the women.

The blacks from Cape Verde were the best and strongest of all, and the most expensive.

The Bantus, of all people, were the most characteristic blacks, but, as we have seen, they did not contain all the African elements imported into Brazil. In addition to the Bantu language, our blacks spoke other languages or dialects of the Sudanese group (Jeje, Hauçá, Nagô or Yoruba).

In this context of diverse origins, the black man adapted to a hard life in Brazil, because let’s not forget that he was a slave and had to obey his master.

Nevertheless, from an early age, the black man demonstrated his strength and will to survive in a strange land that deprived him of his freedom.

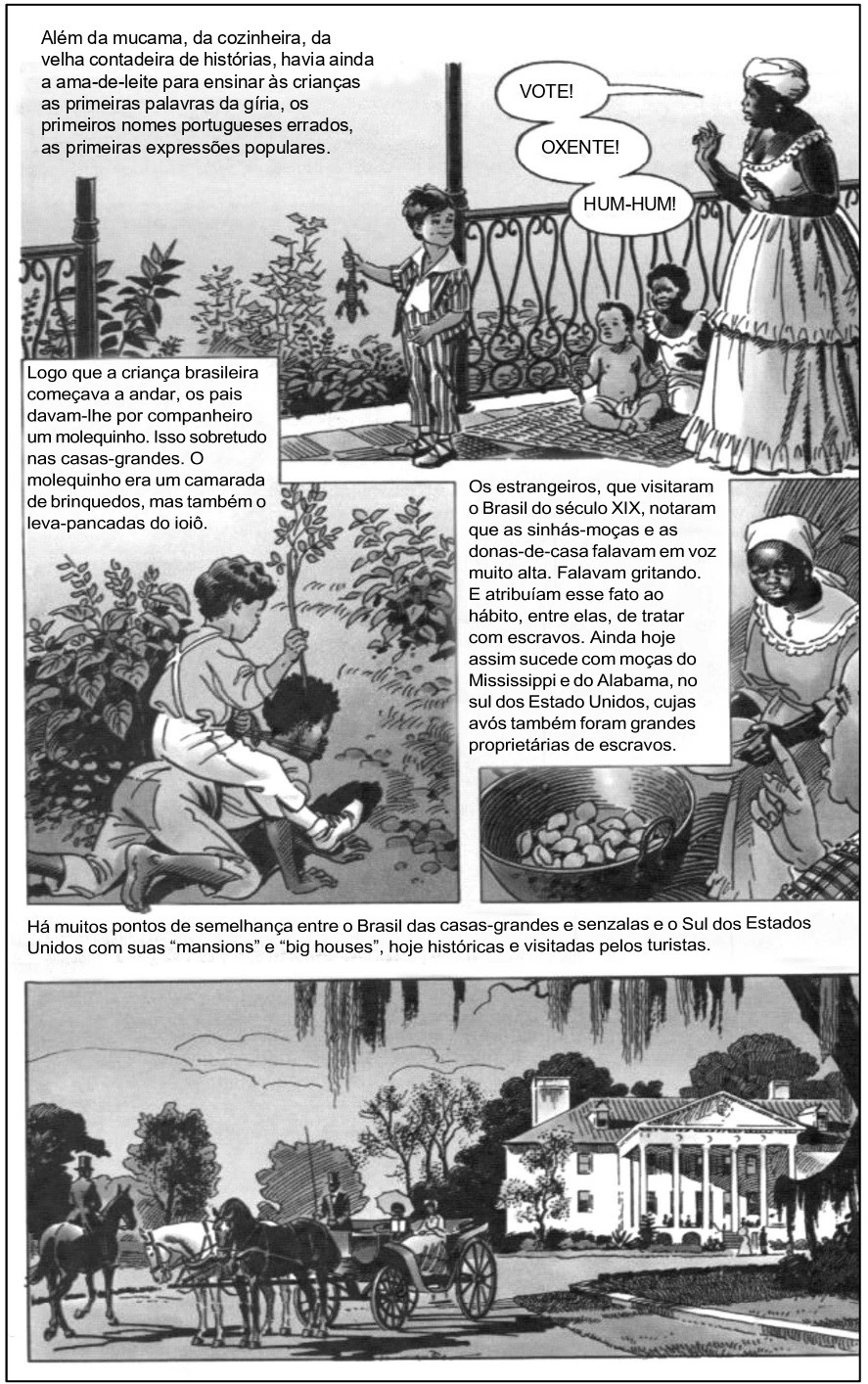

To illustrate this, we will present a fragment from the book “Casa Grande e Senzala“, adapted into a comic strip (2001, p. 38), which problematises everyday life and the relationship between Portuguese and blacks in a colonial sugar plantation in north-eastern Brazil.

What was life like on a sugar plantation in the 16th century, what kind of food did they eat, what were their social relations like, how was their religiosity structured and what kind of problems did they face?

According to Freyre, life on a sugar plantation, and especially food, was difficult because, despite the wealth generated by sugar and the abundance of natural resources, the lords tried to imitate European habits.

The very plantation owners of the colonial period, whom we have become accustomed to imagining through the chronicles of Cardim and Soares, feasting amidst the rich variety of ripe fruit, fresh vegetables and loins of excellent beef, people with a bountiful table who ate like bums – they, their families, their followers, their friends, their guests; the plantation owners of Pernambuco and Bahia themselves ate poorly: Beef of poor quality and only occasionally, little and wormy fruit, rare vegetables.

The abundance or excellence of food, which was surprising, would be exceptional and not general among these large landowners (2003, p. 98).

He also states that:

They had the foolish luxury of ordering much of their food from Portugal and the islands; as a result, they consumed foods that were not always well preserved: meats, cereals and even nuts, which lost their nutritional principles when not spoiled by poor packaging or the circumstances of irregular and slow transport.

Strangely enough, the table of our colonial aristocracy lacked fresh vegetables, green meat and milk. This certainly led to many of the digestive diseases that were common at the time and which many caturra doctors attributed to “bad air” (2003, p. 98).

The following image contradicts the above statement and shows a rich and varied table, which is certainly part of a romantic representation that does not correspond to the reality of colonial Brazil.

To deepen this discussion and make it easier to understand, we present a fragment from the “Golden Book of Brazilian History” by historians Mary Del Priore and Renato Pinto Venâncio (2001, pp. 57-60).

If we accept the opinion of the literary figures of the time, we can say that, despite appearances to the contrary, even the richest peasants ate poorly and ate tough beef.

Only occasionally did they taste fruit. Even more rarely, vegetables.

The lack of good food was compensated for by an excess of sweets: guavas, jams, cashew nuts and sugarcane honey, alfalfa and cocadas.

When a priest passed through, the larders were opened with great effort and the farm animals were killed: ducks, piglets and goats.

In Pernambuco, according to a chronicler, “fishing slaves” were in charge of collecting “all kinds of fish and shellfish” on these occasions.

The abundance recorded in some mills was not the norm. Those who had the luxury of ordering food from the kingdom ate poorly preserved food.

Plantation owners suffered from stomach ailments, which doctors of the time attributed not to poor diet but to the bad air of the tropics. The saúva, floods and droughts made it even harder to find fresh food.

Syphilis ravaged their bodies, leaving scars and wounds.

Most of the sugar mills were located in the forest, not far from the port centres, due to the greater fertility of the land, which was well cloaked in green, and the abundance of firewood needed for the hungry furnaces, which were fed by a workforce that sometimes worked day and night for eight or nine months.

And they didn’t have to move too far from the coast, otherwise, with the same price for export goods, they wouldn’t be able to compete with farmers closer to the market, whose product wouldn’t be affected by transport costs.

In Pernambuco, they settled along the rivers on the Atlantic side of the Borborema plateau, in the Mata zone, where rounded hills and slopes predominate.

The companion of the land was water. If irrigation was no longer necessary thanks to the abundance of the Massapé, both cattle and people needed fresh water. It was also used in the mills, presses and grinders.

No wonder most of the mills were located on the banks of rivers such as the Paraguaçu, Jaguaribe and Sergipe in Bahia, and the Beberibe, Jaboatão, Uma and Serinhaém in Pernambuco.

Inside the real fortresses of adobe and rammed earth that were the great houses, simplicity and even discomfort prevailed.

Furniture was poor and scarce: dressers, chests of drawers, cupboards and hangers. All rough pieces made by the mill worker.

Some preferred the sweetness of hammocks, a refreshing solution on hot nights. Balconies in the middle of the main façade and small verandas gave the mill owner a view of his land, his cane and his people.

The high ground floors, veritable closed warehouses, lit by portholes, allowed them to better defend themselves against the enemy.

However, there was no shortage of contemporary observers who raved about the grandeur of the complex: “a watermill adorned with buildings”, “a mill with large buildings and a church”, “a mill adorned with buildings with a very well arranged chapel and beautiful cane fields”, described the Portuguese chronicler and mill owner Gabriel Soares de Souza in 1587.

The austerity of the house was matched by the extravagance of the clothing on festive days: “They dressed themselves, their wives and children in all sorts of velvets, damasks and other silks, and in this there was much excess […] the bridles and saddles of the horses were made of the same silks in which they were dressed,” commented a distinguished Cardim during the period of sugarcane expansion.

According to Cardim, weddings were celebrated with banquets, bullfights, cane and ring games and wine from Portugal.

Many named their engenhos after patron saints: São Francisco, São Cosme, São Damião and Santo Antônio.

Others had African names – Maçangana. Still others were named after fruits and trees: Pau-de-Sangue, Cajueiro-de-baixo, Jenipapo.

At the centre of his family, the Engenho Lord had to radiate authority, respect and action.

Under his command, children, poor relatives, siblings, bastards, godchildren, confectionery, embroidery – all alternated with devotional practices. In her husband’s absence, however, she took on her work responsibilities with the same vigour as her husband.

At the centre of his family, the Engenho Lord had to radiate authority, respect and action.

Under his command were children, poor relatives, brothers, bastards, godchildren, servants and slaves.

A wife, sometimes much younger, moved in his shadow. She lived to bear children and, in the meantime, carried out domestic activities – sewing, confectionery, embroidery – alternating with devotional practices. In his absence, however, she took on her professional responsibilities with the same vigour as her husband.

Her family was the outward expression of a society, but not the domain of sexual pleasure. The possibility of using female slaves created a racial division of sex in the masters’ world.

The white woman was the housewife, the mother of the children. The natives, and later the blacks and mulattos, were the realm of pleasure.

The occupation of the sugar lands was also marked by disputes over access to the land, and there was no shortage of those who, in the words of one observer in 1635, “cunningly and stealthily” infiltrated the virgin lands in the hope of getting rich by setting up sugar mills.

The sugar mill was an extremely complex structure. A structure that, in its classical form, i.e. associated with large plantations and slave labour, developed in the northeast of Brazil in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Although based on large capital capable of guaranteeing large-scale production, the sugar industry also relied on small entrepreneurs who supplied the sugar mills with sugar cane.

A Dutch report from 1640 states that only 40 per cent of the mills in Pernambuco ground their own cane, the rest relied on the raw material brought in by these farmers.

The sugar business didn’t just involve masters and slaves. It required a diverse group of specialised workers and aggregates who hovered around its fringes, providing their services to the landowner. They were sugar masters, purifiers, wholesalers, caulkers, boilermakers, carpenters, bricklayers, boatmen and others.

They were joined by other groups that animated the economic and social life of the coastal areas: merchants, farmers, artisans, subsistence and sugar cane planters, and even the unemployed formed a complex fragmentation of small and large landowners.

The number of slaves they owned (from two to dozens) allowed us to deduce the diversity of social origins and economic situations.

In the 18th century, with the decline of the activity and the increase of freedmen, some freedmen also became owners of sugar cane farms.

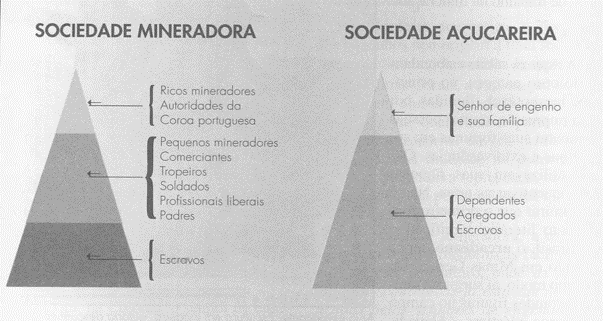

Sugar society was watertight, in other words there was no social mobility. There were basically two social classes: that of the plantation owner and his family, and that of his dependents, the indentured servants and slaves.

In the mining society, which will be studied in the next unit, there was greater social mobility as there were at least three social classes: the rich miners and crown officials; the small miners, traders, muleteers, soldiers, liberal professionals and priests; and finally the slaves.

See the picture below, which shows the two social pyramids. What was the structure of the colonial sugar and mining society in Brazil?

About the Sugar Company, Gilberto Freyre states that

Sugar cane was first cultivated in São Vicente and Pernambuco, and later in Bahia and Maranhão, and wherever it was successful – mediocre, as in São Vicente, or maximum, as in Pernambuco, the Recôncavo and Maranhão – it gave rise to a society and way of life with more or less aristocratic and slave-like tendencies.

As a result, they had similar economic interests.

Later, an economic antagonism would emerge between men with capital, who could afford the costs of sugar cane cultivation and the sugar industry, and those less fortunate with resources, who were forced to spread out into the hinterland in search of slaves – a kind of living capital – or to stay there as cattle breeders.

It was an antagonism that the vast country could tolerate without upsetting the economic balance.

The result, however, was a Brazil that was anti-slavery or indifferent to the interests of slavery, represented by Ceará in particular and by the sertanejo or cowboy in general (2003, p. 93).

Analysing Gilberto Freyre’s view, we can conclude that the sugarcane economy was exclusionary, based on slavery, a factor that hindered the social advancement of free men, forcing them to look for other economic activities in the hinterland.

In the next chapter we will study the Dutch invasion of northeastern Brazil. The study of this invasion is very important because it changed the colonial structure and introduced a new reality into the history of colonial Brazil.

4. In this chapter you have seen

- The importance of the colonial sugar mill in the history of Brazil.

- The main socio-cultural characteristics of the colonial sugar mill.

See the following periods in the history of colonial Brazil:

- Brazilian Independence – Breakdown of colonial ties in Brazil

- Portuguese Empire in Brazil – Portuguese royal family in Brazil

- Transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil

- Foundation of the city of São Paulo and the Bandeirantes

- Transition from colonial to imperial Brazil

- Colonial sugar mills in Brazil

- Monoculture, slave labour and latifundia in colonial Brazil

- The establishment of the General Government in Brazil and the founding of Salvador

- Portuguese maritime expansion and the conquest of Brazil

- Occupation of the African coast, the Atlantic islands and the voyage of Vasco da Gama

- Pedro Álvares Cabral’s expedition and the conquest of Brazil

- Pre-colonial Brazil – The forgotten years

- Establishment of the Portuguese Colony in Brazil

- Periods in the history of colonial Brazil

- Historical periods of Brazil

Publicações Relacionadas

Portuguese maritime expansion and the conquest of Brazil

Carlos Julião: The Military Engineer and Draughtsman Who Portrayed Colonial Brazil

History of the Captaincy of Todos os Santos Bay between 1500 and 1697

The History of the Jews in Colonial Brazil

Monoculture, Slave Labour and Latifundia in Colonial Brazil

History of the sugar mills of Pernambuco - Beginning and end

Pedro Álvares Cabral's expedition and the conquest of Brazil

History of the Fortresses and Defences of Salvador de Bahia

Pre-colonial Brazil - The forgotten years

The history of sugar cane in the colonisation of Brazil

Transition between colonial and imperial Brazil

Portuguese Empire in Brazil - Portuguese Royal Family in Brazil

Foundation of the city of São Paulo and the Bandeirantes

The occupation of the African coast and Vasco da Gama's expedition

The Origin of Sugarcane and Sugar Mills in Colonial Brazil

Establishment of the Portuguese colony in Brazil

Transfer of the Portuguese court to colonial Brazil

Shipwreck of the Galeão Sacramento in Salvador: Learn the story

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français