Popular art from the Northeast of Brazil reflects the vastness of its territory and the diversity of its culture, and some types of work can be found, with slight variations, in all the states.

While relying on tradition, popular art of the Northeast discovers new languages, techniques and materials: the ability to reinvent itself is proof of its inexhaustible vitality.

The craft production of the North-East reflects the size of its territory and the diversity of its culture.

All along the northeastern coast – and in various parts of the interior, especially in the towns on the banks of the São Francisco River – you’ll find women, leaning on cushions or wooden frames, wielding needles or bobbins, producing fine weavings like those brought by the first Europeans to arrive in the colony.

These are weavings and embroideries with names such as labirinto, boa-noite, filé, redendê – depending on the technique – that usually leave the coastal villages for the fashion circuit of the Brazilian capitals.

VIDEO ABOUT THE FOLK ART OF THE NORTHEAST

Literatura de Cordel08:45

Centro de Artesanato de Pernambuco12:47

Renda de bilro em Aquiraz05:33

Garrafas de areia coloridas03:42

Artesanato de Maragogipinho02:25

NORTH-EASTERN FOLK ART

- LACE

- STRING LITERATURE

- WOOD ART

- CERAMICS AND CLAY DOLLS

- COLOURFUL SAND BOTTLE ART

- MARAGOGIPINHO HANDICRAFTS IN BAHIA

- BETWEEN TRADITION AND MARKET

THE WORK OF THE GROUP, THE WORK OF THE ARTIST

There are crafts whose authorship dissolves in the collective and there are those that bear the mark of the craftsman.

The masks, costumes and embroidered dresses used in Carnival, the bumba-meu-boi and the folias-de-reis, as well as the clothes and objects used in Afro-Brazilian rituals or the puppets called mamulengos, are made by artists who are almost always anonymous.

On the other hand, in Caruaru, in the Agreste region of Pernambuco, Vitalino Pereira dos Santos (1909-63) gave the clay figures typical of the region a style and language of their own, depicting scenes from everyday life in the Sertanejo; he created a legion of followers and lived up to the title of “master”.

Today, his children and grandchildren continue his work, and the district where he was born, Alto do Moura, is considered by Unesco to be the greatest centre of figurative art in the Americas.

Not far away, in the Zona da Mata region of Pernambuco, pottery is also a source of income for more than half the population of the town of Trucunhaém.

The researcher Lélia Coelho Frota points out that while the thematic axis of Caruaru ceramics is the documentation of everyday life, Trucunhaém’s is essentially focused on the sacred and solemn, visible in the saints sculpted by Maria Amélia and Zezinho and the magnificent lions by Master Nuca (1937-2004).

1. LACE

Lace is also a popular craft in the North East and can be found on clothing, scarves, towels and other items. It plays an important economic role in the north, north-east and south.

Cushion or bobbin lace is made by the hands of a lace maker using a cushion, perforated cardboard, thread and bobbins (small wooden pieces resembling spindles).

Brought by the Portuguese and Azorean settlers, this technique is a traditional work from different parts of the Brazilian coast.

Lace is passed down from generation to generation, and some designs are exclusive to one family. Although lace is not originally a Brazilian product, it has become a local product through acculturation.

BOBBIN LACE IN CEARÁ

Bobbin lace is a textile craft whose historical origins date back to the 15th and 16th centuries, with Flanders and Italy claiming paternity. Flanders claims to be the inventor of bobbin lace and Italy claims the patent for needle lace, which gave rise to Renaissance lace.

The first category of lace is that made from a bobbin, known as bobbin lace.

The bobbin is a small instrument consisting of a short rod with a spherical tip.

A quantity of thread is attached to the other end of the bobbin, which the artisan attaches to a standard design or drawing of the lace to be made.

The production of this type of lace requires the use of several bobbins, the number of which varies according to the complexity of the design. Bilro lace is made on pillows placed on the weaver’s lap or on a wooden easel in front of her.

The thread used by bobbin lace makers is cotton, and the colour used is usually white, both because it’s traditional and because it’s easy to see. The shape used is called “pique”.

The designs are old and have been passed down from generation to generation. To get new designs, lacemakers borrow piques from each other or get samples from other places. Some rare lacemakers make the lace from scratch, without using a mould.

The resulting lace can take many different forms:

- beaks or tips, used to decorate the edges of fabrics or to be placed between two pieces of fabric

- bedspreads, tablecloths, centrepieces and napkins

- Lace in the shape of flowers, hearts, fans, etc., applied to fabrics to decorate them.

- Palas: whole pieces worn over the neckline of sweaters, blouses and dresses.

Lace and embroidery are the predominant handicrafts in Ceará, present in about 104 municipalities.

According to the Ceará Handicraft Centres Monitoring System (SAC-CEART), 700 artisans are registered for the “bobbin lace” typology, of which 99.4% are women and 0.6% are men.

Records show that this type of craft has existed in Ceará since colonisation and has spread to the interior and coastal areas, mainly concentrated in the municipalities of Aquiraz, Aracati, Beberibe, Acaraú and Trairi.

The development of handicrafts can become a hallmark of the region. This is what is happening in the Prainha district, with its lace, located in the municipality of Aquiraz.

The municipality of Aquiraz has been in existence for more than three centuries and has an estimated population of 72,628. Its strong tourist appeal and a

history of handicrafts stand out as important characteristics.

2. CORDEL LITERATURE

Perhaps nothing is more typical of the popular art of the Northeast than cordel literature.

In the pamphlets sold in the streets and markets of the Sertão, literature and images intersect in cordel literature: on the covers, woodcuts illustrate the verses, which range from love stories and folk legends to social denunciation and political criticism.

Pernambuco’s Bezerros, a neighbour of Caruaru, calls itself the “capital of the cordel” and is home to some of its biggest names, starting with the octogenarian J. Borges, poet, singer and illustrator.

The same tradition survives in Juazeiro do Norte, in Ceará, where the mythical master Noza (1897-1984), also a sculptor, lived: there are now workshops in the city where craftsmen reproduce his famous images of Father Cícero carved in wood.

3. WOODWORK

In addition to the images of Father Cícero in Juazeiro do Norte, there is a tradition of art and woodwork related to religious imagery in the Northeast.

In Cachoeira, in the Recôncavo Baiano, Louco – the name by which the sculptor Boaventura da Silva Filho (1932-92) became known – made a name for himself by producing Catholic saints and orixás, elongated images of great impact.

As tradition dictates, Louco’s craft has been passed down to his fans and students, and today sacred pieces are produced in the city’s workshops by Louco Filho, Doidão, Dory and Mimo.

In Triunfo, Pernambuco, Chico Santeiro carves images of St Francis, St Peter, St Anthony and Our Lady, dressing them in luxurious clothes.

In Acari, Rio Grande do Norte, Ambrósio Córdula also makes wooden saints, cribs and angels.

Religiousness is also present in the ex-votos, a tradition dating back to the 18th century, which unfortunately seems to be dying out.

The old panels painted with scenes of miraculous healings are no longer produced; wooden images, usually of parts of the body, carved in gratitude for some grace received, have survived and can still be found in the so-called “miracle rooms” of churches, sanctuaries and pilgrimage centres.

Today, Aberaldo, from the island of Ferro (Alagoas), gives a new dimension to the ex-votos by colouring them and transforming them into decorative pieces.

The mysticism of the Sertanejo is also reflected in the famous frowns with which the boatmen of the São Francisco River tried to ward off the evil spirits that might threaten their journey.

In Santa Maria das Vitórias, Bahia, Francisco Biquiba dy Lafuente Guarani (1884-1987) created some of the most remarkable ones. In the 1960s, carrancas became a decorative craze throughout the country and began to be produced on a large scale – losing some of the strength of the originals – in towns along the river, especially in Petrolina, Pernambuco.

Wood is also the raw material for everyday objects, furniture and toys. In the same Acari where Mestre Ambrósio makes his saints, Manuel Jerônimo Filho makes exquisite lorries.

In Maranhão, Nhozinho (1904-74) transformed the malleable wood of the buriti tree into small dolls representing the typical characters and bumba-meu-boi figures of the state; his work can be seen in São Luís, in the museum that bears his name.

Other Northeastern pine trees provide raw materials for artisans in the interior and on the coast: carnauba fibre is used by the inhabitants of the Parnaíba Delta in Piauí to make baskets, objects and ornaments; ouricuri straw is used by artisans on the coast of Alagoas to make rugs, bags and hats.

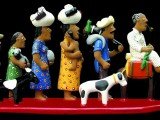

4. POTTERY AND CLAY DOLLS

Pottery is one of the most developed forms of popular art and craft in Brazil. Divided into utilitarian and figurative ceramics, the art of the Indians was later mixed with the European clay tradition and African patterns, and developed in regions favourable to the extraction of its raw material – clay.

In the fairs and markets of the northeast you can see clay dolls representing typical characters of the region: cangaceiros, retirantes, merchants, musicians and lace makers. The most famous are those of Mestre Vitalino (1909-1963) from Pernambuco, who left dozens of descendants and students.

Figurative ceramics also stand out in the states of Pará, Ceará, Pernambuco, Alagoas, Sergipe, Bahia, Espírito Santo, São Paulo and Santa Catarina. In the other states, ceramics are more utilitarian (pots, pans, vases, etc.).

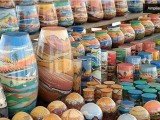

5. COLOURED SAND BOTTLE ART

This art form is widespread in northeastern Brazil, especially in Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará, the birthplace of its creator, where many artisans make a living making and selling these pieces.

The production of coloured sand bottles, also known as cyclogravure, began in the 1950s on the beach of Majorlândia in Ceará, where a woman named Joana Carneiro filled bottles with sand of different colours, collected from the hills of the region. As she filled them, she arranged the colours in a circle, leaving about two centimetres between each portion of sand she filled.

On one occasion she was filling a litre of these sands when, just before she finished, the litre tipped over. As the container wasn’t completely full, the sands spilled over the side and accidentally formed a drawing that looked like a landscape to the eyes of a son who was present at the time.

The lady’s son was Antônio Eduardo Carneiro, who later became known as “Toinho da Areia Colorida” for his ability to “draw with sand”. He was responsible for creating the first landscapes in bottles of coloured sand.

Although they are called “coloured sand bottles”, they can be made in other containers such as goblets, tulips, bulbs and various other types and shapes of containers, as long as they are made of transparent, uncoloured glass so that the colours of the sands can be fully appreciated.

The vast majority of the sands used in this work are naturally coloured. Only the green and blue colours are made from white sand with the addition of dyes. Lighter or darker shades are obtained by mixing existing colours.

The price of the pieces varies according to the size of the container and the complexity of the design. The more elaborate the design, the higher the price. Smaller pieces cost around R$10.00 each. Larger pieces can cost up to R$1,000.00 or more.

6. MARAGOGIPINHO HANDICRAFTS IN BAHIA

The pieces produced in Maragogipinho have a very high cultural value and a great potential for growth and appreciation. The quality of the pieces is increasingly attracting new consumers.

Most of the pieces made in Maragogipinho are unmistakable because they are finished with tauá, a clay-based engobe rich in iron oxide that gives the pieces a reddish colour.

Another local characteristic is drawing with tabatinga, a white liquid clay that is very abundant in the region.

Thousands of utilitarian and decorative pieces are made in Maragogipinho, with a production volume of around 18,000 pieces per month. These pieces are distributed to various Brazilian states, such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Goiás, Santa Catarina, Ceará, Paraná and the Federal District.

The objects, whose shapes show clear indigenous, African and Portuguese influences, vary greatly in size and shape. We can find objects from 2 centimetres to over 1.50 metres high.

The craftsmen and women still use the crude tools of centuries ago, such as the wooden lathe.

Every month they model, decorate and fire a wide variety of pieces. There are moringas, pots, carvings, porrões, bilhas, panela, vasos, pratos, xícaras, tigelas, jarros, luminárias, esculturas sacras, objects de decoração, among others.

The excellence of Maragogipinho’s ceramics has been recognised.

In 2004, the community exported a container of pieces to Europe, and two of its pieces competed for the UNESCO Crafts Prize for Latin America and the Caribbean.

The boi-bilha, a piece that combines the figure of the northeastern ox with the Portuguese bilha, received an Honourable Mention from the UN.

In partnership with export companies, more than 40,000 pieces have already been exported and are circulating in countries such as Germany, Spain and Italy.

To promote their products, the Maragogipinho community not only participates in fairs throughout Brazil, but also relies on the help of organisations such as SEBRAE to make big sales. The most recent sale was to the Tok Stok shop, which sold over a thousand pieces.

This strengthens the community as the quality of products for this audience is very demanding.

7. BETWEEN TRADITION AND THE MARKET

Popular art, both a cultural expression and a source of income, moves between the reproduction of traditional knowledge and the discovery of new techniques and materials.

In the Northeast, crafts handed down from generation to generation adapt to circumstances and the urgency of survival.

In Acari, Dimauri Lima de Souza transforms old cars into dolls and toys.

The coloured sand used to make landscapes in bottles, a typical souvenir from Ceará, is now obtained thanks to the use of industrial dyes – there was a time when only the coloured sand from the dunes of Majorlândia, on the east coast of the capital, was used.

In Santana do Cariri, in the interior of the same state, the town council encourages the making of replicas of fossils in order to prevent the predatory sale of the local archaeological heritage.

The countless objects that make up what is vaguely called Northeastern handicrafts – cloths, hammocks, miniatures, toys, drawings, ex-votos, saddles, leather, ornaments, utensils – are reproduced every day.

Folk art of the Northeast

Publicações Relacionadas

Graciliano Ramos: A Literary Icon of Brazilian Northeastern Life

History and Chronology of the Carnival of Salvador de Bahia

Origin and History of Acarajé - a speciality of Afro-Brazilian cuisine

History of Afro-Brazilian Religions: Candomblé and Umbanda

Itineraries for Religious Tourism in Salvador

Bahia joins the ethnic tourism route

Musical styles, rhythms, singers and composers of northeastern Brazil

Monte Pascoal National Park: Pataxó culture and Brazilian history

Bobbin lace and embroidery: predominant handicrafts in Ceará

History and Chronology of the Portuguese Tile Industry

Colours of houses and buildings in the colonial architecture of the northeast

Monte Santo in Bahia: History and Religious Tourism

Biography of Victor Meirelles and analysis of the work "The First Mass in Brazil"

The rhythm of Candomblé in Bahia

Exploring Capoeira in Salvador: A Martial Art Rich in History

Rural Maracatu: A carnival tradition in the interior of Pernambuco

Discover the Magic of Iemanjá Festival in Salvador de Bahia

The origin of the Afro hairstyle in Salvador

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français