For more than three hundred years, Minas Gerais supported the Portuguese crown, helped build the idea of an independent Brazilian nation and always managed to remain influential in Brazilian political decisions.

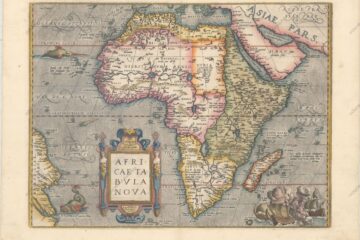

In the beginning, it was the interior.

In the first centuries of colonisation, the territory that we now call Minas Gerais was, in the eyes of the colonisers, a vast expanse of cliffs and impenetrable forests inhabited by unknown creatures – it is estimated that at the time of the arrival of the Europeans (1500), a hundred indigenous groups lived in the region.

It was a threatening territory, but it was also full of promise: it was hoped that the continent would contain the metals and precious stones that motivated the conquistadors; there would certainly be slave labour for the sugar cane plantations that were expanding in the coastal areas during the first century of colonisation.

And so began the epic voyage of discovery of Portuguese America, with the aim of capturing the indigenous population and discovering its mineral wealth.

Expeditions organised by the government and private individuals travelled across Brazil, expanding its borders.

From São Paulo, explorers travelled over the Mantiqueira mountain range to reach what was then known as the Cataguás interior (named after the Indians of the region); from Bahia, they travelled along the Jequitinhonha River and the banks of the São Francisco River.

However, it wasn’t until the end of the 17th century that the first significant sample of gold was found, near the Velhas River, close to present-day Sabará.

The news spread throughout the colony. Minas Gerais was born.

HISTORY OF MINAS GERAIS

1. GOLD EXPLORATION

The announcement of the first finds sparked a desperate rush to the mining region.

Adventurers came from all over the colony, inspired by the dream of easy riches: the exploitation of Minas gold, found in the beds of rivers and streams, required no major capital investment.

The region also welcomed thousands of Europeans; some 600,000 Portuguese landed in Portuguese America in the first sixty years of the 18th century.

The population explosion, coupled with the precariousness of supply routes, plunged the Land of Gold into chaos. Starvation plagued the region, and masters and slaves went so far as to eat pack animals and insects.

In 1707 the Paulistas, the discoverers of the mines, clashed with the Portuguese and settlers from other captaincies – whom they pejoratively called Emboabas, meaning “foreigners” – for control of the gold-mining area.

The Emboaba War lasted two years and culminated in the massacre of the Paulistas.

After the confrontation, the Portuguese government created the Captaincy of São Paulo and Minas do Ouro to guarantee the exploitation of a territory that was proving to be unmanageable; many Paulistas, in turn, moved west to Goiás in search of new deposits.

In the midst of conflicts and tensions, a new society was consolidated in the mining region.

During the first half of the 18th century, subsistence farms were established and roads were opened to connect the mining area with the colony’s coast. Those who didn’t have their own sources of supply were subject to the extremely high prices charged by the merchants – tropeiros – who brought food from the south and Bahia.

For the first time, the colony was integrated.

2. A NEW SOCIAL ORDER

As new veins of gold were discovered, the miners founded settlements that soon became populated towns: Caeté (1701), Conceição do Mato Dentro (1702), São José del-Rei, now Tiradentes (1702), São João del-Rei (1704), Vila Rica, now Ouro Preto (1711), Mariana (1711), Sabará (1711), Congonhas do Campo (1734), Paracatu (1798).

Merchants, artisans, doctors, lawyers and officials involved in the management and control of the mines circulated in these towns.

And prisoners: in the middle of the 18th century, there were around 100,000 slaves of African origin in Minas Gerais.

It was not uncommon for masters to offer small prizes in gold to encourage them to work in the mines, or for slaves to hide the metal in their pockets or under their fingernails until they had collected enough to buy their freedom.

In this way, black slaves became part of the urban scene, often becoming small traders.

The influx of Europeans, settlers from different regions, blacks and Indians led to a process of mestizaje unprecedented in the colony.

3. UNDER THE CONTROL OF THE PORTUGUESE CROWN

For almost a century, the Portuguese colony revolved around the gold economy.

The Portuguese crown, drowning in debt, set up a gigantic apparatus to monitor and collect taxes.

At first, miners owed Portugal a fifth of all the gold they found.

Later, the government set a minimum amount to be collected.

If the required quota wasn’t reached, a derrama – a state of emergency – would ensue, during which collectors would enter homes and confiscate property.

In 1720, the greed of the Portuguese crown led to the first rebellion of the settlers of Minas Gerais.

The uprising, which took place in Vila Rica, was quickly crushed and one of its leaders, the muleteer Filipe dos Santos, was executed.

In a new attempt at control, the government separated Minas and São Paulo, creating the Captaincy of Minas Gerais, with its capital in Vila Rica, now Ouro Preto.

In 1727 it was announced that diamonds had been found in the arraial of Tijuco, now Diamantina, in the mountains known as Serro Frio.

It is likely that miners had discovered the stones a decade earlier, but they didn’t make the news public so as not to upset the tax authorities.

With good reason: the rules in what became the Diamantino district were even stricter than in the gold-producing areas.

For a hundred years, no one was allowed to move in the district without official permission.

See also Historical Towns of Minas Gerais.

4. INCONFIDÊNCIA MINEIRA

As time went on, the urbanised society of Minas Gerais became culturally richer.

Brought from Europe, Baroque took on its own characteristics in the colony and became the first indigenous art form. The sons of wealthy families went to European universities and returned with new ideas, including that of a republic.

In 1789, in the same Vila Rica that had witnessed the death of Filipe dos Santos, a group of intellectuals, merchants, miners and landowners, indebted and angered by the threat of a tax, conceived a revolt that would establish the independent Republic of Minas Gerais. Denounced, the inconfidentes were arrested, some were deported, others had their property confiscated.

Only Ensign Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, known as Tiradentes, was hanged and quartered in April 1792.

Many years later, the Brazilian Republic elevated him to the rank of martyr and included him in the gallery of the country’s heroes.

5. AN AGRARIAN STATE

At the end of the 18th century, gold began to run out. The exploitation of deep mineral deposits required capital and technical expertise that did not exist in Brazil.

In search of new deposits of gold and precious stones, or space to raise cattle, explorers moved into the hinterland, founding towns and defining the borders of the captaincy: the north and north-east, close to the Jequitinhonha valley, which belonged to Bahia, were annexed to Minas at the turn of the 19th century; the triangle, disputed with Goiás, was annexed to Minas in 1815.

Soon, the Captaincy was no longer the land of gold; the towns emptied out.

The production of goods to supply the former mining towns and Rio de Janeiro, which became the seat of the Portuguese crown and later the Brazilian government, boosted the local economy.

Cattle ranching spread to the south of Minas and was joined by the dairy industry and coffee growing. At the end of the 19th century, the bankrupt mines were bought by English companies, which exploited them until they were exhausted.

Supported by the rural elite, the province of Minas Gerais continued to exert its influence throughout the 19th century.

In 1842, liberals from Minas Gerais and São Paulo, disgusted by the conservative influence of the rural elite on the central government, launched the Liberal Revolution.

In São Paulo, the movement was crushed in June; Minas, under the command of Teófilo Otoni, resisted until August, when it surrendered to the troops of the Duke of Caxias in the town of Santa Luzia.

The strength of the mining oligarchies continued after the Republic.

From 1894, politicians from Minas and São Paulo alternated in power in a pact known as the café com leite policy.

In the same decade, the state capital was moved from Vila Rica to the newly built Cidade de Minas, which later became Belo Horizonte. Between 1898 and 1930, three of the eleven presidents elected came from Minas Gerais.

When the alliance between the rural oligarchies broke down, the miners allied with the gauchos in the 1930 revolution that brought Getúlio Vargas to the presidency and ended the First Republic.

In 1937, Getúlio Vargas staged a coup d’état and established his dictatorship, the Estado Novo.

Minas Gerais, which supported the rise of Getúlio Vargas, also worked to overthrow him, publishing the Miners’ Manifesto in 1943, a document that called for a return to democracy, which would happen in 1945.

The 1940s also saw a change in the economic scenario, with the creation of Companhia Vale do Rio Doce to exploit iron ore – the state returned to mining in a new way.

6. JUSCELINO KUBITSCHEK

Born in Diamantina, Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira was a federal deputy, mayor of Belo Horizonte and state governor between 1934 and 1954.

In the capital, he left his mark with the construction of the Pampulha complex, designed by Oscar Niemeyer.

Elected president in 1955, the following year he launched an ambitious plan to industrialise the country and develop its automotive industry.

In the same year, Juscelino began building the country’s new capital, Brasilia, again designed by Lúcio Costa and Niemeyer and inaugurated in 1960.

The price of modernising euphoria was Brazil’s debt and rising inflation.

Nevertheless, the years of Juscelino Kubitschek’s government (between the mid-1950s and the early 1960s) are marked in Brazilian history as one of the most optimistic periods, when people believed in the formation of a modern, democratic country – a dream that would be shattered a few years later, in 1964, when a coup d’état established the military dictatorship in Brazil.

The tanks that would end the democratic period came from the Juiz de Fora garrison.

One of the main organisers of the coup was the governor of Minas Gerais, Magalhães Pinto. During the dictatorship, Minas Gerais experienced a surge in development, with the expansion of mining and steel complexes and the establishment of an automotive centre in Betim.

7. REDEMOCRATISATION

Twenty years later, when the military dictatorship began to yield to the pressures of Brazilian society, another Minas Gerais politician was at the forefront of organising the civilian return to power: in January 1985, Tancredo de Almeida Neves, Juscelino’s trusted man, was elected president by the National Congress.

Shortly before being sworn in, Tancredo fell seriously ill and his vice-president, José Sarney, took over. The country watched in disbelief as he died on 21 April, the day Tiradentes was executed.

A few years later, Minas Gerais would have another president: Itamar Franco, Fernando Collor’s vice-president, took office in 1994 when Collor, accused of corruption, lost his mandate.

Under Itamar’s government, the then finance minister Fernando Henrique Cardoso launched the Real Plan to curb inflation. The plan’s success guaranteed Fernando Henrique the presidency in 1996.

In the 21st century, Minas Gerais is the second most industrialised state in Brazil; it is the country’s largest producer of iron ore, niobium, zinc and gold; agriculture and cattle ranching predominate in the south and southeast regions and in the Triângulo Mineiro.

History of Minas Gerais

Publicações Relacionadas

Church of St Francis of Assisi - Ouro Preto: History, architecture and art

Diamantina - Tourist Attractions, History and Architecture

Royal Road Route - History, routes and attractions

Ouro Preto: Historic City of Tourist and Cultural Interest

Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Matozinhos - History and Architecture

São João del Rei MG - Attractions, History and Architecture

Tourist Attractions and History of the Caraça Sanctuary MG

Aleijadinho: Biography and works that shaped the Brazilian Baroque

Little Church of Pampulha MG: history, architecture and religious importance

Sabará: A Journey Through Its Rich History

Mariana: A journey through time to colonial Brazil

Tourist Attractions and History of Serro in Minas Gerais

Pico do Itacolomi - Attractions, history and itineraries

Baroque of Minas Gerais in Focus: History, Techniques and Works

Tourist attractions and routes in Serra do Cipó MG

History and Monuments of Tiradentes MG

Catas Altas MG - History and Monuments

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français