The Iberian Union and the Dutch Invasion of Brazil

1. introduction

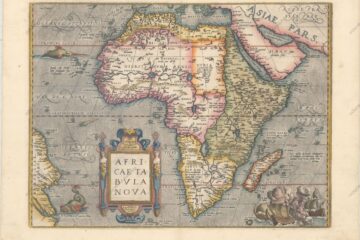

In the first part of this chapter we will study the so-called “Iberian Union”, which was the union of the Portuguese and Spanish crowns. This was due to the death of the king of Portugal, whose closest relative was the Spanish king Felipe II, who was crowned king of both crowns.

In the second part of this chapter, we will show that the dynastic union between Portugal and Spain was the stimulus for the so-called Dutch invasions of Brazil, as the Spanish closed Brazil to Dutch trade. This period is also referred to by historians as “Spanish Brazil” and “Dutch Brazil”.

União Ibérica e a Invasão Holandesa no Brasil

2. Iberian Union or Spanish domination

In the second half of the 16th century, the Avis dynasty, which had ruled Portugal for more than 200 years, seemed to be running out of steam. By this time, only King João III and his brother, Cardinal Dom Henrique, were still alive.

For a better understanding of this issue, see part of the text “O domínio holandês no Brasil 1630-1654” by historians Mozart Vergetti de Menezes and Regina Célia Gonçalves (2002, pp. 9-10). Below is an extract from the text.

Portugal, a kingdom without a king.

Dom João III had seen the deaths of his nine male children and was anxiously awaiting the birth of a grandson to ensure the continuity of his line. If this didn’t happen, Portugal risked falling into foreign hands.

The old king died a few months before the birth of Dom Sebastião, whose pregnancy had been accompanied by much prayer on the part of the Portuguese people.

The new monarch took office at the age of 14. He dreamed of organising crusades against the Muslims and spreading the Christian faith.

Since Dom Sebastião was very young, he didn’t want to marry and continue the dynasty.

In 1578 he prepared an expedition to conquer Morocco. But his army was weak and poorly organised and was quickly destroyed by the Muslims.

In the battle of Alcácer Quibir, Dom Sebastião died, along with much of the Portuguese nobility.

King dead, king made.

When Dom Sebastião died, his great-uncle, the aforementioned Cardinal Dom Henrique, took over the throne.

At a very advanced age, he didn’t last long in power, dying two years later.

The Portuguese nation lost the last representative of the Avis dynasty and saw the beginning of the struggle for the Portuguese throne, which would not end until 1580.

As we have seen in the text “Portugal, a kingdom without a king”, Portugal’s doors were open to Spanish domination, since the closest relative of the deceased king, Dom Henrique, was Felipe II of Spain.

Despite this, several candidates came forward to claim the Portuguese crown. Among the candidates were Don Antonio and Felipe II, King of Spain, who claimed the right to the Portuguese kingdom because he was the grandson of a former King of Portugal called Don Manuel.

Antonio had the support of the people, who did not want to see the throne handed over to a foreigner.

Philip II, a staunch Catholic and naturally opposed to the Christian reformers, had the full support of the clergy and much of the nobility, as well as the bureaucrats and merchants.

In June 1580, the Duke of Alba, the best general in the Spanish Empire, invaded Portugal with a strong army and put an end to Don Antonio’s pretensions, securing the Portuguese crown for Philip II, who was renamed Philip I in Portugal.

Thus began the Habsburg dynasty in Portugal.

Philip II was succeeded by two more Felipees, the second (third in Spain) in 1598 and the third (fourth in Spain) in 1621, who remained in power in Portugal until 1640.

It was during the latter’s reign that the Dutch invasion of Brazil took place (MENEZES; GONÇALVES, 2002, p. 10).

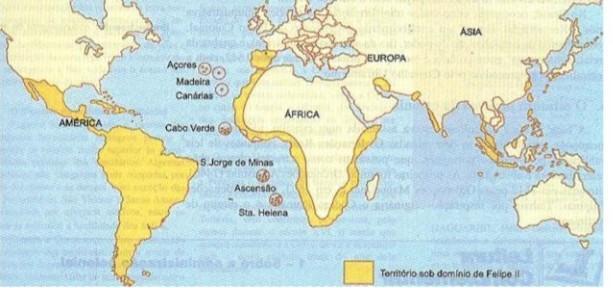

In this sense, Portugal would remain under Spanish rule for sixty years. At that time, Spain became the largest empire in the world, as it united its colonies with those of Portugal.

For Brazil, the Iberian Union was healthy, as it cancelled the borders of the Treaty of Tordesillas and allowed Brazil to establish the outlines of its current borders.

According to Eduardo Bueno (2003, p. 85):

Under Philip II, and then under his successor Philip III, Brazil was able to move from a “regional” position, that of a mere supporting player in the game of commercial exchange, to a new and more honourable geopolitical role, integrating itself into the fabric of the Atlantic empire conceived by Philip II.

Between 1580 and 1615, Brazil also expanded internally: Paraíba and Maranhão were definitively conquered, two dozen settlements were founded, new trade routes were opened, new public offices were created, and the link between southern Brazil and the Plata region was definitively established.

In addition, the focus of economic activity shifted from agriculture and the extraction of plants to the search for mineral wealth – a profound change in the course and destiny of the future nation.

It was also during Felipe’s reign that the bandeirantes of São Paulo operated with an ease that would have been difficult to imagine outside a period when the borders of the Spanish and Portuguese possessions were not so intertwined.

When the Iberian Union came to an end, with the fragile reign of Felipe IV and the Portuguese Restoration, the vast territory conquered by the bandeirantes became part of Brazil.

Although fundamental to the country’s history, the Felipe period remains one of the least studied in Brazil.

It was only after the Iberian Union that the São Paulo bandeirantes began to have a more constant presence in Brazilian history. Later, it was the São Paulo bandeirantes who were responsible for the discovery of gold in the hinterland of Minas Gerais.

In the next section we’ll look at the Dutch invasion of northeastern Brazil.

3. Dutch invasions of Brazil

The Dutch had always been trading partners with the Portuguese, but during the period of the Iberian Union they planned and carried out two invasions of the colony.

The first Dutch invasion took place in Salvador in 1624 and 1625, but the Portuguese soon expelled the invaders.

The second Dutch invasion lasted longer and had a greater impact on Brazilian history. It took place between 1630 and 1654 and covered almost the entire northeast.

According to Mozart Vergetti de Menezes and Regina Célia Gonçalves (2002, p. 4):

The period of Dutch rule in Brazil, and the struggle to end it, has been a recurrent theme in Brazilian history, fuelled by the imagination of the local population and elites, and often revisited by different historians from different eras.

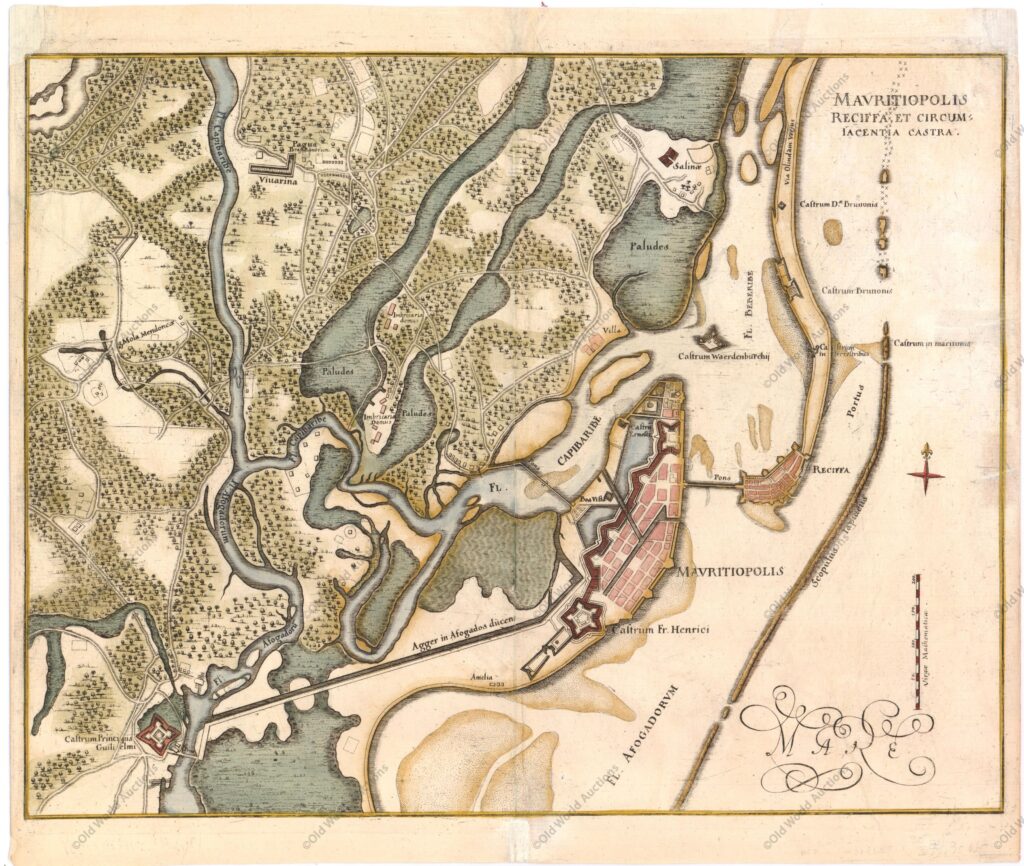

Some highlight the cultural richness of the period, especially during the administration of Count João Maurício de Nassau-Siegen, who, with his court of artists, architects, cartographers, naturalists, etc., promoted, among other things, the transformation of the city of Recife into the most urbanised city in the Americas in just seven years.

Idealising this moment, some say that it would have been better for the northeast not to have returned to Portuguese rule.

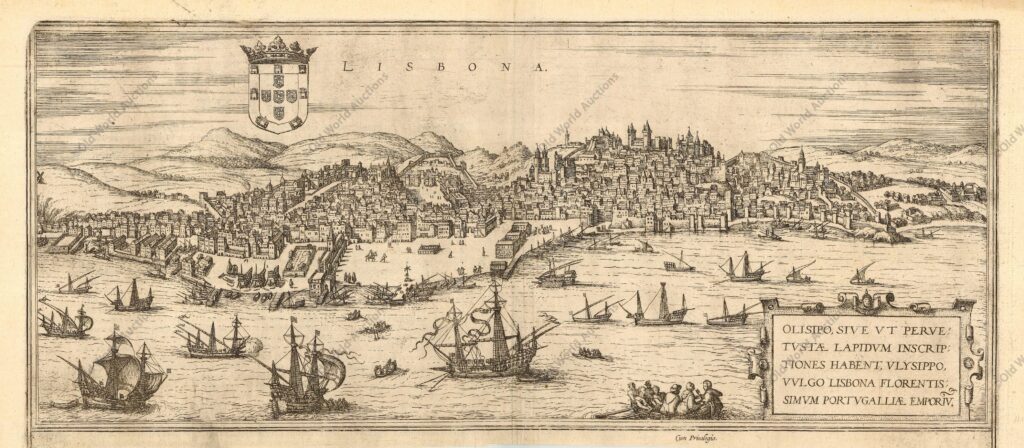

Before the advent of the Iberian Union, Portugal and the Netherlands, also known as the United Provinces, had flourishing trade relations.

Flemish and Dutch ships docked in Portuguese ports. These ships unloaded a wide variety of goods, such as wheat, fish, butter and cheese, and imported coarse salt from Portugal.

The port of Antwerp received spices and other products from the East, as well as sugar and timber from Brazil (MENESES; GONÇALVES, 2002).

When Philip II of Spain declared war on the United Provinces, he cancelled all these traders’ contracts with Portugal.

This not only restricted the import of products that were vital to the survival of the Portuguese people, but also jeopardised important activities in the Dutch economy, since coarse salt from Portugal was essential both for the preservation of Dutch fish and for the production of dairy products.

Faced with a shortage of wheat, the grain used to make bread, the Portuguese population put pressure on the Spanish court to give in and reopen the treaties that had previously existed between the two countries.

This led to a truce, the Twelve Years’ Truce, which restored Portuguese-Dutch trade. This truce, which lasted from 1609 to 1621, gave the Dutch the opportunity to intensify their contacts with Brazil.

The Dutch had been frequent visitors to the Brazilian coast since the 16th century.

The earliest record of their presence in Brazilian ports dates from 1587, when a 250-tonne Flemish-flagged ship was captured in Bahia during an attack by English privateers.

There are also reports of a sugar mill acquired by an Antwerp banker at the end of the 16th century under the captaincy of São Vicente – the Engenho dos Erasmos – as well as a record of the Portuguese ship São João, which left Brazil in 1581 with a total of 428 boxes of sugar, 350 of which belonged to three Flemish merchants and a German.

During the Twelve Years’ Truce, the Dutch devoted themselves to the sugar trade and shipped more than 50,000 boxes of the product every year.

When the truce expired in 1621, the Dutch merchants felt that all their hard work would come to an end, and they did everything they could to prevent this from happening.

Having already seen the success of the East India Company, they decided to create another company, the West India Company, which would raise capital and unite the merchants involved in the sugar trade to fight the Spanish and continue in such a lucrative business (MENEZES; GONÇALVES, 2002, pp. 14-15).

With the end of the truce in 1621, the Dutch merchants decided to take hitherto unthinkable measures, as they could not afford the losses resulting from the closure of the Portuguese and Brazilian markets.

These unprecedented measures were to invade the north-east of Brazil. The Dutch therefore began to organise the invasion, targeting the city of Salvador, the capital of the colony.

3.1 First Dutch invasion: Salvador

The first invasion took place on 4 May 1624. The Dutch organised a powerful fleet of 28 ships, manned by some 3,300 men.

The invaders soon took the city and arrested its governor, Diego de Mendonza, who was deported to Holland.

However, in July 1624, Dutch Admiral Jacob Willekens, commander of the squadron, decided to return to Holland, leaving about a third of his forces in Bahia.

This proved to be a strategic mistake, as the Portuguese and Spanish would soon send forces to retake the city.

When, in April 1625, the Portuguese-Spanish armada, commanded by Dom Fradique de Toledo, arrived in São Salvador, consisting of 31 galleons, several caravels and 7,500 armed men, the Dutch forces found themselves in a difficult situation.

Portuguese and Spanish troops stationed themselves at the entrance to the Bar and set fire to the Dutch ships. With frequent attacks on land, the enemy forces were undermined until finally, in early May, the Dutch troops were forced to surrender.

Under the terms of the capitulation, all weapons were to be handed over to the victors and the Dutch were allowed to return to their country in the ships they had left behind (MENEZES; GONÇALVES, 2002, p. 17).

The first Dutch invasion of Brazil was a disaster. It also cost the West India Company dearly. Decades later, the Dutch would again invade northeastern Brazil, but this time they would be more successful, staying for about 24 years.

3.2 Second Dutch invasion: Pernambuco

The Dutch invasion of Bahia in 1624 failed due to a number of factors explained in the previous section.

Despite this, the Dutch didn’t give up their project to invade northeastern Brazil, which was part of the Dutch intention to dominate sugar production, the kingdom and trade in Europe.

According to Eduardo Bueno (2003, p. 91):

The invasion of Bahia brought only losses to the nascent West India Company. In 1628, however, the company captured the annual Spanish silver fleet off Cuba and made a haul of 14 million florins (double its initial capital).

Enriched, the company planned another invasion of Brazil.

This time the target was the largest and richest sugar-producing region in the world.

Not only did Pernambuco have 130 sugar mills (responsible for a thousand tonnes of sugar a year), but it was a private, not a royal, captaincy and therefore poorly equipped for defence.

On 15 February 1630, an armada of 77 ships, 7,000 men and 170 pieces of artillery appeared off Olinda.

Although the resistance of Governor Matias de Albuquerque (grandson of the old grantee Duarte Coelho) was once again heroic – he even managed to set fire to 24 ships anchored in the harbour before leaving – Recife was quickly taken.

This time the occupation would last more than 20 years.

As we have seen, the captaincy of Pernambuco was very rich and its sugar production was the largest in the world, so it was no wonder that the Dutch chose this region.

Over the next twenty-four years, much of northeastern Brazil would come under Dutch rule.

For many, it would have been more advantageous for the Northeast if the Dutch had not been expelled, as it was under Dutch rule that this region became the most urbanised and prosperous in the Americas.

The Dutch rule in Pernambuco can be divided into three phases:

- The first, from 1630 to 1637, was marked by the resistance of the Luso-Brazilians, who fought against domination in the interior;

- The second phase, from 1637 to 1644, was the period of Dutch Brazil. During this period, the main urbanisation works in Recife were carried out by Maurício de Nassau;

- The third phase, from 1644 to 1654, was marked by the War of Reconquest, which resulted in the expulsion of the Dutch.

It is important to emphasise that the most important phase of Dutch rule in northeastern Brazil was that represented by the administration of Count Maurício de Nassau.

He arrived in Brazil in 1637 and soon proved to be a great administrator. Through his mediation, the Luso-Brazilians were pacified and began to sell their sugar production to the Dutch.

The main measures taken by the Dutch government were

- The granting of loans to mill owners, which were used to re-equip the mills, restore the cane fields and buy slaves, thus reactivating sugar production.

- Religious tolerance: The different religions (Catholicism, Judaism, Protestantism) were tolerated to a certain extent by the government of Maurício de Nassau-Siegen. The Dutch did not seek to spread their religious beliefs in Brazil. However, the official religion of Dutch Brazil was Calvinism, and this was the religion most promoted.

- Urban works: The city of Recife benefited from the construction of bridges and sanitary works. The city of Maurícia, now a district of the capital of Pernambuco, was also created.

- Cultural life: The Nassau government encouraged the arrival of artists, doctors, astronomers and naturalists. Among the painters were Franz Post and Albert Eckhout, authors of several paintings inspired by Brazilian landscapes. In the scientific sector, Jorge Marcgrave, one of the first to make use of our nature, and Willen Piso, a doctor who researched cures for the most common diseases in the region, stand out.

See also Recife dos Holandeses.

As a result of all these measures, Nassau’s government was very prosperous, as it was at this time that Dutch Brazil reached its greatest splendour.

Despite the successful experience of Nassau’s government, after his departure there was a change of mentality in the way the colony was governed. The other rulers who succeeded Nassau radically changed their behaviour, causing discontent among the Luso-Brazilian population.

The West India Company, which was only interested in increasing its profits, began to put pressure on the plantation owners to increase production, pay more taxes and pay off their debts.

The West India Company threatened to confiscate the owners’ mills if their demands were not met. Even religious tolerance had come to an end. Catholics were forbidden to practise their religion freely (COTRIM, 1999, p. 104).

Angered by the Dutch pressure on the way the colony was administered, groups of Brazilians and Portuguese began to revolt, demanding that the invaders leave the northeast of Brazil. This happened in 1645 and was called the Pernambuco Uprising.

It’s interesting to note that this movement brought together different sectors of Brazilian society who began to fight side by side: plantation owners, slaves and Indians.

Some historians claim that the movement that led to the expulsion of the Dutch from Brazil was the first expression of Brazilianness and identity in Brazilian history. This movement demonstrated the maturity of the colony, as it was the Brazilians themselves who were most committed to the expulsion.

The expulsion of the Dutch, which was finalised in 1654, created another problem for Portugal, because when the Dutch left Brazil they took with them sugar cane seedlings to plant in the Antilles, a region in the Caribbean.

The Dutch decision to produce sugar led to a serious crisis in Brazil, as the sugar produced in Central America had a lower selling price than that produced in the northeast of Brazil. In addition, this sugar created competition, since until then only Brazilian sugar had been sold in Europe.

Portugal therefore realised that it had to encourage the inhabitants of Brazil, especially the bandeirantes who lived in São Vicente and São Paulo, to undertake expeditions to find precious metals in the Brazilian interior.

Brazil could not rely on sugar cane alone to fuel its economy.

The incentive given to the bandeirantes would bring a return to the Crown and they would soon discover gold in the Minas Gerais.

4. Historical events related to the Iberian Union and the Dutch invasions of Brazil

- 1566-1609: Dutch war of independence against Spain.

- 1578: Defeat of Alcácer-Quibir, death of Dom Sebastião, King of Portugal.

- 1580: Beginning of the Iberian Union, which lasted until 1640.

- 1602: The Dutch East India Company is founded.

- 1609: Signing of the “12 Years’ Truce” between Holland and Spain.

- 1621: The Dutch West India Company is founded. Beginning of the reign of Philip III in Portugal (Philip IV in Spain).

- 1624: First Dutch invasion: capture of Salvador.

- 1625: The Luso-Spanish Armada commanded by Dom Fradique de Toledo recaptures Salvador.

- 1630: Dutch invasion of Pernambuco: conquest of Olinda and Recife.

- 1631: Evacuation of Olinda and Recife by the Portuguese-Brazilians.

- 1633: Dutch conquest of Itamaracá and the Reis Magos fort.

- 1634: Conquest of Paraíba by the Dutch.

- 1636: Battle of Mata Redonda, with victory for the Dutch.

- 1637: Arrival of Maurício de Nassau-Siegen in Recife, beginning of the Nassau reign.

- 1639: Foundation of the city of Mauritius.

- 1640: End of the Iberian Union.

- 1641: The Dutch conquer Maranhão and Sergipe.

- 1643: Portuguese Restoration.

- 1644: Nassau returns to Holland.

- 1648: First battle of Guararapes.

- 1649: Second battle of Guararapes.

- 1654: Surrender of the Dutch in Recife.

In the next chapter we will study the founding of the city of São Paulo and the settlement and colonisation carried out by the bandeirantes.

5. In this topic you have learnt that

- The historical process determined the Iberian Union.

- The Dutch invaded Brazil and stayed until 1654, when they surrendered in Recife.

Publicações Relacionadas

History of Bahia in Colonisation, the Empire and the Republic

Chronology of slavery in colonial and imperial Brazil - History

Chronology of Portuguese discoveries and maritime expansion

Defences of Porto da Barra - Fortifications of Santa Maria and São Diogo

Historical periods of Brazil - Colonial period to the New Republic

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français