Brazilian Independence – The End of Colonial Ties in Brazil

1. introduction

As you may have noticed, we have presented a reading of various factors related to the emancipation of Portuguese America.

The growth and diversification of society, the establishment of the Portuguese Court in Brazil, and the protest movements are thus a series of events that help us to better understand the political and economic majority in Brazil.

In this theme, however, we will look at some significant episodes from the last years of the colonial period, in order to complement our lessons on the process of struggle against Portugal’s domination of Brazil.

First of all, we can say that the “Grito do Ipiranga” was a symbolic and political gesture by the then Prince Regent Dom Pedro, who officially established Brazil’s independence.

This event, which served to formalise emancipation, was also a way for the Brazilian aristocracy to remain in power.

The act of proclaiming Brazil’s independence was an agreement between the national elite and the monarch.

Even the date of Brazil’s independence can vary.

Although Dom Pedro proclaimed independence on 7 September 1822, the Bahians dated Brazil’s liberation as 2 July 1823, when Portuguese troops led by Madeira de Melo were defeated by Brazilian forces financed by the plantation owners and commanded by Lord Cochrane.

Portugal, for its part, did not formally recognise Brazil’s independence until August 1825, when the Brazilian government compensated the former metropolis.

At the time, Portugal received 2 million pounds.

This was the first episode of a new dependency: Brazil’s foreign debt.

But that’s another story. Let’s go back to 1817, when the people of the northeast fought for the liberation of Brazil, which will be discussed in the next section.

2. The revolution in the north-east

As you already know, the 18th century saw economic growth in the southeast.

Mining transformed the capitals of Minas and Rio de Janeiro. On the other hand, the former sugar cane region experienced a serious financial crisis.

In fact, there was economic inequality between these two regions: the southeast and the northeast.

In addition to the situation of regional inequality in the productive economy, the population at that time had to pay high taxes: to support the high expenses of the Court (which was not satisfied with the substantial donations from the Luso-Brazilian elite) and to finance the military campaigns of the Portuguese Empire.

Jurandir Malerba (2000, p. 242) shows us a specific case of court expenditure, but one that had important consequences for Rio’s economy.

The year 1819 saw the total strangulation of the edible food market at the Court, creating a more than embarrassing situation for the rulers.

The population of Rio de Janeiro, facing the greatest food crisis in living memory as a result of famine and rising food prices, angrily demanded that the King take immediate action.

The Marquis of Valada produced a detailed report to His Majesty explaining the reasons for the inflation, which was particularly serious in the case of poultry for court consumption, which the Portuguese court could no longer supply.

The lack of poultry on the market was just one of the consequences of the high consumption of the entourage of the nobility and the royal family in Brazil.

However, this case is a good example of the situation of the population, which had to pay high taxes not only to finance the daily expenses of the court, but also to pay for the infrastructure works of the new kingdom.

In the north-east, on the other hand, some specific factors – such as the cost of financing the war – had a decisive influence on the uprising of 1817.

In the northeast, against a background of declining sugar and cotton production, the court in Rio de Janeiro was as unpopular as in Lisbon.

The taxes introduced in 1812, the contributions – including manpower – to the troops of the Guiana campaign (invaded at the end of 1808 in retaliation for the Portuguese occupation and to guarantee the frontiers established by the first Treaty of Utrecht) and the worsening of the social situation with the drought of 1816 favoured the spread of liberalism.

You may have noticed that we’ve returned to the subject of liberalism.

We introduced liberal ideas in previous chapters when we referred to the movements that challenged the absolutist regime and mercantilist policies.

The “anti-Lusitanian” movement in Pernambuco was also supported by the Freemasons.

Among the Masonic lodges in Pernambuco, the Areópago de Itambé stood out (see “Conspiração dos Suassunas“).

Liberalism – can be summarised as the postulate of the free use of property by each individual or member of a society.

The fact that some people have only one property: their labour, while others own the means of production, is not denied in liberal ideology, it is just omitted.

In this sense, all men are equal, a fact enshrined in the fundamental principle of the bourgeois constitution: all are equal before the law, the concrete basis of the formal equality of the members of a society.

As an extension of this, a second idea proposes the common good (the commonwealth), according to which social organisation based on property and freedom serves the good of all.

A corollary of this proposition is that, since there is no antagonism between social classes, action can be guided simply by reason – hence rationalism.

This is the core of the ideological proposition that aims at the consensual domination of the workers through the operation of identifying the interest of the ruling class (the maintenance of the existing social order) with the interest of society as a whole – the nation.

In this sense, the factors that triggered the revolution of 1817 had been forming since the conspiracy of 1801 (that of the Suassunas).

But it was triggered by the events of that time. Specifically, the economic crisis and social discontent.

The combination of two economic factors was decisive in mobilising the rural aristocracy: the fall in the price of sugar and cotton on the international market and the rise in the price of slaves.

Meanwhile, the revolution in Pernambuco, which broke out in March 1817, united various social classes (military, landowners, judges, artisans, merchants and priests) who were dissatisfied with the privileges granted to the Portuguese.

The Brazilian military was particularly unhappy because the best command posts were reserved for the Portuguese.

Anti-Portuguese sentiment spread from Recife to other cities: Alagoas, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte.

Boris Fausto (2007, p. 129) describes the outcome of the revolution as follows

The revolutionaries took Recife and set up a provisional government based on an “organic law” that proclaimed the republic and established equal rights and religious tolerance, but did not touch the problem of slavery.

Envoys were sent to the other captaincies in search of support, and to the United States, England and Argentina, also in search of support and recognition.

The rebellion advanced through the interior, but soon the Portuguese forces attacked, starting with the blockade of Recife and the landing in Alagoas.

The fighting took place in the interior, revealing the lack of preparedness and the divisions among the revolutionaries.

In the end, Portuguese troops occupied Recife in May 1817.

This was followed by the arrest and execution of the leaders of the rebellion. The movement lasted more than two months and left a deep mark on the Northeast.

3. The Liberal Revolution of Oporto

The Oporto Liberal Revolution was an event that took place in Portugal in 1820.

A Revolução Liberal do Porto

But despite the vast distance between the Iberian Peninsula and the New Continent, the impact of this movement was decisive in Brazil’s final act of independence.

And once again, liberal ideas provided the backdrop to this revolution.

In fact, Portuguese discontent began with the arrival of the Court in Brazil.

The absence of the king and the administrative apparatus of the monarchy created a state of political uncertainty in Portugal.

The void left by King João was filled by a “Council of Regency” led by the English marshal Willian Carr Beresford (who led the expulsion of the French from Portugal).

The English marshal caused great discontent in the army by preventing Lusitanian soldiers from holding high military posts.

The commercial privileges granted to England with the opening of Brazilian ports were another cause of discontent among the Portuguese.

The aims of the rebels were to limit English influence on the nation and to resume colonial relations with Brazil by reinstating the colonial pact.

But times were different and it would have been difficult for the Brazilian elite to accept such an agreement, don’t you think?

Consider the significant changes that had taken place in Brazil since the arrival of the royal family.

Would you agree that by 1820 Brazil was less a colony and more an empire?

The colonial pact – a system that lasted in Brazil until 1808, it governed the political and economic relations between the colony and the metropolis.

Below are the main points of this system:

- The colony could only trade with the metropolis.

- The colony had to supply goods at a price set by the metropolis.

- The colony had to produce what the metropolis produced.

- The colony had to consume what the metropolis produced.[/box]

In addition to the above demands, the Portuguese revolutionaries demanded the immediate return of the Court to Portugal.

They wanted to restore the monarchy, but on the condition that the king would be subject to a constitutional charter.

The revolutionaries formed the “Provisional Junta of the Supreme Government of the Kingdom”, a heterogeneous group made up of representatives of the clergy, the nobility and the army.

In Brazil, meanwhile, two groups began to struggle: those in favour of the return of Dom João VI, the “Portuguese faction”, “made up of high-ranking military officers, bureaucrats and merchants interested in subordinating Brazil to the metropolis, if possible according to the standards of the colonial system”.

The other group, which came to be known as the “Brazilian party”, was made up of large landowners from the captaincies close to the capital, bureaucrats and members of the judiciary born in Brazil.

There were also Portuguese whose interests were linked to those of the colony: merchants who had adapted to the new conditions of free trade, and investors in land and urban property, often linked by marriage to the people of the colony.

The interests of the Portuguese elite in relation to Brazil became clear in the episode of the Porto Revolution. Opposing groups formed there, both for and against the king’s departure.

The court that accompanied the royal family took root in Brazil and formed a powerful group opposed to the return of King João VI.

The tense relationship between this elite and those who remained in Portugal culminated in 1820. That year saw the beginning of the Porto Revolution.

It was a liberal movement that aimed to set up a constituent assembly but demanded the immediate return of the king to the metropolis.

Even after the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution, the monarch remained a symbolic and real reference point for power in both Portugal and Brazil.

On the other hand, the bourgeois classes in both countries (merchants, bankers, liberal professionals, etc.) organised themselves to approve a constitution (a document that would regulate the kingdom’s governmental policy in the form of laws).

Thus, while certain practices continued as before – such as the worship of the king – others changed as the bourgeoisie sought legitimate ways to exercise power within the monarchical regime.

In April 1821, after thirteen years in Brazil, the king returned to Portugal.

His return was accompanied by about 4,000 people.

His son Pedro (de Alcântara Francisco António João Carlos Xavier de Paula Miguel Rafael Joaquim José Gonzaga Pascoal Cipriano Seraim de Bragança e Bourbon), the future Dom Pedro I, remained in Brazil.

During 1821 there were heated debates at the Portuguese court.

In general, the fate of Brazil was discussed. In these debates, the Court sought ways to regain control over the colony.

The plan was to abolish the hereditary captaincies and establish provincial governments that would report directly to Lisbon.

The aim was to take away the powers previously granted to Rio de Janeiro. In fact, they were thinking of ways to recolonise Brazil.

4. Resistance in Brazil

Despite the manoeuvres of the Portuguese court, there were politicians in Portugal who defended Brazilian emancipation. Among them was José Bonifácio de Andrada, who came from a family of wealthy merchants from the city of Santos.

He was educated at the University of Coimbra, where he graduated in law, philosophy and science. In Brazil, he became the most important minister in Pedro’s government.

José Bonifácio directed his administration towards making Brazil an active and independent nation: he wanted to put an end to the slave trade and free the slaves; he wanted to integrate the freedmen and the Indians into the Brazilian nation; he wanted to confiscate the property of the Portuguese who had not chosen Brazil; he wanted to review the land grants made during the colonial period, recovering all unproductive lands for the Crown; he wanted to move the capital to the centre-west, encouraging the development of the interior.

José Bonifácio refused to take out international loans so as not to create debts that would have to be paid by future generations; he proposed the creation of a navy capable of protecting Brazil’s vast coastline and keeping the other provinces under the control of the metropolis.

He was a man of remarkable vision, and the fate of our country would have been different if his ideas had succeeded. But José Bonifácio’s bold projects ran up against powerful interests.

He angered wealthy Portuguese merchants, slave traders and landowners. And he also fought with the radicals, those who wanted to establish democracy in Brazil.

We can see that José Bonifácio’s thinking oscillated between progressive ideas in the social field and conservative ideas in the political field.

At the same time as defending the abolition of slavery, he also defended a representative monarchy (in which an assembly would be formed made up of deputies indirectly elected by the dominant groups of the population).

José Bonifácio led the movement to create the Brazilian Constituent and Legislative Assembly. This proposal, however, came after the famous “Dia do Fico”.

On 9 January 1822, Dom Pedro I decided to remain in Brazil, in defiance of the Portuguese court’s demands that he return to Europe. This date became known as the “Dia do Fico” (Day of Fico).

The records of the Senate of the Chamber of Deputies of Rio de Janeiro show that when the stay was formalised, the President of the Senate of the Chamber of Deputies raised a series of cheers from the palace windows, which were repeated by the people: “Long live religion, long live the constitution, long live the Cortes, long live the constitutional king, long live the union of Portugal and Brazil”.

At first, Dom Pedro’s act was not aimed at Brazilian independence, as the prince was following the guidelines of the so-called “Coimbra Elite” (a group formed at the University of Coimbra that wanted to bring about political reforms in Brazil and thus prevent its definitive separation from Portugal).

This group had a grandiose ideal: to build a Portuguese empire that would integrate Brazil and Portugal.

However, the plans of this illustrious elite did not succeed. The Portuguese troops left Rio de Janeiro after attempting to embark the prince for Portugal.

There was resistance and, with the support of the people, Dom Pedro refused to take his place alongside Dom João. The Portuguese army had no choice but to leave Brazil, taking the news of the latest events with them.

5. Grito do Ipiranga – Long live the King, long live Brazil

Less than a year after “Dia do Fico”, Brazil’s independence was formalised.

The episode went down in history as the Grito do Ipiranga (Cry of Ipiranga), when the then 24-year-old Prince Dom Pedro proclaimed Brazil’s independence on the banks of the Ipiranga River.

But it wasn’t until December 1822 that he was crowned king, in a religious but essentially political ceremony.

Dom Pedro’s coronation had an important political and cultural function in the nascent kingdom.

The coronation of Dom Pedro I took place in Rio de Janeiro on 1 December 1822, after the various acclamations, the inauguration of the Chambers and the beginning of the War of Independence.

The date was cleverly chosen because it was the day on which the Portuguese celebrated the end of Spanish rule.

It was a way for Brazil to tell Portugal that it was no longer a colony and would submit to its rule, just as Portugal had become independent from Spain.

The introduction of the coronation distinguished the Brazilian monarchy from the Portuguese and was a completely new rite for the Brazilian dynasty.

This rite transcended the recognition of men, since the sovereign received a task prescribed by God in the Church, like a bishop.

This gesture strengthened the mystical union between the people and the sovereign, precisely because it had always been inscribed in the divine plans – as Bro Sampaio commented in the coronation sermon in the Royal Chapel.

We can’t help but think that a crowned monarch would have been more acceptable to the black, African and liberated classes, who worshipped the feast and the kingdom of the Divine Holy Spirit and the kings of the Congo – thus facilitating his reception.

This passage from the book “The Independence of Brazil” by Iara Souza brings us face to face with an important symbolic ritual: the coronation of the king.

Today, in our society, we witness and/or participate in a series of rituals: baptisms, debutante balls, weddings, funerals, etc.

These rituals serve to mark a moment of transition, of change in our lives, but they can also legitimise the power of a leader.

In our presidential system, for example, the elected candidate officially becomes president after receiving the presidential sash from the previous head of state.

The celebrations can therefore also be seen as a legitimation ritual, in other words an event to promote a particular personality.

Although Pedro proclaimed independence in 1822, Brazil’s emancipation actually took place over a longer period.

For didactic purposes, we can say that Brazil’s independence took place between the arrival of the Court and its proclamation (1808 – 1822).

Thus, we have independence as a process that involved different characters, both national and foreign. In fact, we should remember that a nation becomes “independent” only in relation to other countries, in opposition to them or in alliance with them.

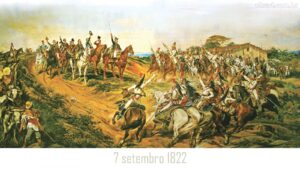

5.1 Pedro Américo’s painting “Independence or Death”, 1888

Pedro Américo’s painting ‘Independência ou Morte’ (Independence or Death), painted in 1888 and better known as ‘O Grito do Ipiranga’ (The Cry of Ipiranga), shows Pedro I in the centre, raising his sword on the banks of the Ipiranga River and proclaiming Brazil’s independence (7 September 1822), with the knights of his retinue on the right and the soldiers curiously watching the scene on the left.

The work was commissioned by Emperor Pedro II to glorify Dom Pedro I, to commemorate the birth of the nation and the Brazilian Empire, to link the decline of the Brazilian monarchy with the proclamation of the Republic, and to invest in the construction of the Ipiranga Museum in São Paulo, the Paulista Museum, where the painting is now located.

The image symbolises the proclamation of Brazil’s independence, consecrated on 7 September, but does not accurately represent the moment when D. Pedro I returned from São Paulo, received the letter from Portugal and proclaimed Brazil’s independence.

The scene was created by Pedro Américo’s imagination, since it would be impossible to establish a real link between the painting and the events, due to the great difference in time (the painting was done in 1888 and independence took place in 1822) and the lack of reports.

There are significant contradictions: it was not appropriate to make long journeys on horseback, but with mules; the clothes worn by the prince and his retinue were too gallant for the journey; the retinue was not so numerous and there is no record of the prince uttering the phrase “Independence or Death”.

The painting depicts the episode in a grandiose way, not imitating reality but recreating ideal beauty, praising the Empire and the nationalism of Brazil, which had recently proclaimed its independence.

6. The action of secret societies

The study of the societies that existed in Brazil from the end of the 18th century requires an analysis of their true role in our political movements.

A Maçonaria e a Independência do Brasil

In fact, the very existence of most of these societies is known only through their political action.

Some developed more or less rapidly because of the principles they embodied, the organisation they adopted and the projection of their members.

However, the model of a secret society that has played a decisive role in our history is that of Freemasonry.

Today, it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to determine how these societies functioned or whether they had objectives other than those stated in their programmes.

Freemasonry, gardening and charity had as their aim the improvement and preservation of the human species, and had nothing to do with business, religion or politics.

But the Apostolate is all purely political; for its end is to constitute the Empire of Brazil in a way that I will say. [According to A Sentinela de Liberdade, from Pernambuco, number 47, it is a club of corrupt or stupid aristocrats, propagators of the evil faith of absolutist monarchy, despotism and cruel tyranny, with the aim of preserving a branch of the Braganza dynasty, absolute and arbitrary, so that we can be whipped with the irons and bones of our ancestors, who suffer so much for being weak.

According to Frei Caneca himself, this society also operated in Rio de Janeiro.

While other societies, secret or not, operated in the country itself, with a regional scope, Freemasonry developed throughout the colony, coming from the Kingdom, directly or not, and above all from French and English universities.

This international character gave it strength and prestige, especially in Brazil.

Its origins are practically unknown, as the Freemasons themselves, who have discussed the subject, don’t agree.

Of all these discussions, the most probable is that it was originally linked to the ancient brotherhoods of Freemasons, hence the name.

These brotherhoods had initiation rites and building secrets that were naturally confined to the circle of initiates.

Leaving aside the question of its origins, which does not concern us directly, let’s focus on the undeniable fact of the great development that Freemasonry began to undergo in the 18th century and the important impact it had throughout the world at the end of that century and the beginning of the 19th.

Among the principles considered sacred by Freemasonry, there is a whole individualistic liberal philosophy, which originates from the Enlightenment of the 18th century or results from a convergence in the same direction.

According to the Masonic Syllabus, freedom of thought and rationalism are the fundamental principles of society.

Freemasonry accepts members of all religions, and its concept of the “Great Architect of the Universe” has no connection with the belief in God in the various religions.

With liberal-democratic ideals – the motto of liberal-democratic revolutions: liberty, equality, fraternity, is of Masonic inspiration – Freemasonry will maintain a political position characterised by the fight against absolute powers. It is in this position that we find an explanation for the great spread of Freemasonry.

The proliferation and consequent development of lodges for political purposes in France and other absolutist countries was a response to the status quo.

Indeed, the ideological principles of Freemasonry, which correspond to the individualist liberal ideology, will define the interests of the rising bourgeoisie.

That’s why, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Freemasonry was adopted and accepted by all those who didn’t want to be seen as reactionaries.

Organised ideologically, Freemasonry then took a decidedly revolutionary stance against the absolutist powers.

As an ally of the liberal movements, the secret society would also seek to make its presence felt in the great political events that could bring about a transformation capable of affecting the absolute monarchies.

In this way, it would not only turn its members into revolutionaries, but would also try to attract people capable of exercising political power.

Thus, in our country, Pedro I became a Freemason, not so much because he embraced the ideals of Freemasonry, but because it was in the interest of Freemasonry to make him a Freemason.

It is impossible to say exactly when Freemasonry arrived in Brazil, as there is no consensus even among Freemasonry historians. We can find various reports of its presence as early as 1788, but there is no known document that confirms this.

It is certain, however, that Freemasonry must have been introduced along with the Enlightenment ideas acquired by Brazilian students in Europe, who often continued their studies in France and England after graduating from the University of Coimbra.

The University of Montpellier, considered one of the Masonic centres of the time, was one of the most frequented by Brazilian students.

It was attended by José Joaquim da Maia, Álvares Maciel, Domingos Vidal Barbosa and others.

In 18th century Europe, Freemasonry developed and gained prestige thanks to the rise of the bourgeoisie and the spread of Enlightenment ideas, while in Brazil the absence of a bourgeoisie as a class prevented a similar process.

What Freemasonry will reach in Brazil, therefore, is not the class that is most accessible to it in the Old Continent.

Here, the privileged are the sons of gentlemen, the sons of those landed aristocrats who study at European universities.

It is only they who will have the opportunity to discover the philosophy of illustration; it is only they who will be able to bring the books of Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu and others to Brazil and, given the relationship between Freemasonry and illustration, it is only they who will be initiated into Freemasonry.

Let’s also not forget the liberating objective that society acquired in the American colonies.

It was therefore interesting that these settlers who went to Europe to educate themselves also learned about secret societies, not only because it gave them prestige and brought them up to date with current socio-political changes, but also because it made them interested in the liberation of their country.

7. You have seen this in this chapter:

- The period between the arrival of the Court and the proclamation of Brazil’s independence represents a transitional space between the colony and the Brazilian Empire.

- Brazil’s independence was the result of a political, economic and cultural process.

- Pernambuco’s reaction to the economic inequalities between the north-east and south-east regions led to an important anti-Lusitanian movement.

- The liberal revolution in Porto led to the return of Dom João VI to Portugal (1821) and the proclamation of Brazil’s independence.

See the following periods in the history of colonial Brazil:

See the following periods in the history of colonial Brazil:

- Brazilian Independence – Breakdown of colonial ties in Brazil

- Portuguese Empire in Brazil – Portuguese royal family in Brazil

- Transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil

- Foundation of the city of São Paulo and the Bandeirantes

- Transition from colonial to imperial Brazil

- Colonial sugar mills in Brazil

- Monoculture, slave labour and latifundia in colonial Brazil

- The establishment of the General Government in Brazil and the founding of Salvador

- Portuguese maritime expansion and the conquest of Brazil

- Occupation of the African coast, the Atlantic islands and the voyage of Vasco da Gama

- Pedro Álvares Cabral’s expedition and the conquest of Brazil

- Pre-colonial Brazil – The forgotten years

- Establishment of the Portuguese Colony in Brazil

- Periods in the history of colonial Brazil

- Historical periods of Brazil

Publicações Relacionadas

Portuguese maritime expansion and the conquest of Brazil

The Origin of Sugarcane and Sugar Mills in Colonial Brazil

Sugar Mills in Colonial Brazil: A Historical Insight

Pre-colonial Brazil - The forgotten years

History of the Fortresses and Defences of Salvador de Bahia

Portuguese Empire in Brazil - Portuguese Royal Family in Brazil

The history of sugar cane in the colonisation of Brazil

The occupation of the African coast and Vasco da Gama's expedition

Transition between colonial and imperial Brazil

Shipwreck of the Galeão Sacramento in Salvador: Learn the story

Pedro Álvares Cabral's expedition and the conquest of Brazil

Learn about the periods of Brazil's colonial history

Foundation of the city of São Paulo and the Bandeirantes

Dutch Invasion of Salvador in 1624: Overview

The History of the Jews in Colonial Brazil

History of the sugar mills of Pernambuco - Beginning and end

Installation of the General Government in Brazil and foundation of Salvador

Transfer of the Portuguese court to colonial Brazil

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français