Pedro Álvares Cabral ‘‘s Expedition and the Conquest of Brazil

1. introduction

In this chapter we begin our study of the “discovery” of Brazil.

The word “discovery” is inappropriate because before the Portuguese arrived in the region we now call Brazil, it was inhabited by a wide variety of peoples.

In this sense, Brazil was not discovered but conquered.

We will study the organisation of the Portuguese squadron commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral, as well as some of the daily life of the voyage that led to the “discovery”.

We will also discuss the process of conquest and the cultural contact between the colonising Portuguese and the colonised native “Indians”.

Indian – the term was born out of a historical error, because Christopher Columbus thought he had discovered India when he discovered America.

From then on, the term became popular. Over time, other names have been coined for the Indians: aboriginal, Amerindian, autochthonous, Brazilian Indian, gentile, Indian, black of the land, native, buggy, savage, among others.

2. The expedition of Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral’s expedition is credited with the “discovery” of Brazil, but some historians claim that Brazil had been discovered several years earlier by both the Portuguese and the Spanish.

As Grandes Navegações, Parte 11 - Pedro Alvares Cabral, A descoberta do Brasil

On this subject, Boris Fausto (2007, p. 30) states that:

Since the 19th century, it has been debated whether the arrival of the Portuguese in Brazil was the work of chance, brought about by sea currents, or whether there was already prior knowledge of the New World and Cabral was given some kind of secret mission that would lead him to take the western course.

All the evidence suggests that Cabral’s expedition was indeed destined for the Indies. This rules out the possibility that European navigators, especially Portuguese ones, had visited the Brazilian coast before 1500.

In any case, this is a controversy of little interest today, belonging more to the realm of historical curiosity than to the understanding of historical processes.

Regarding this controversy, Eduardo Bueno (1998, pp. 32-33) states that

In any case, whether King Dom João II knew of the existence of Brazil or not, what is certain is that in the second half of 1497, when he was sailing towards India, Vasco da Gama had already sensed the existence of these same lands.

In fact, on 22 August of that year, after setting sail from the Cape Verde Islands towards India, Gama and his men saw seabirds flying “very hard, like birds going ashore” in the middle of the sea.

Vasco da Gama couldn’t change course to follow them, but the sighting was recorded in his log.

At the time, the Portuguese navigators were interested in the real India – which they knew lay to the east, beyond the Atlantic Ocean – not the lands Christopher Columbus was discovering to the west.

In June 1499, as soon as Vasco da Gama arrived in Lisbon with the long-awaited news that India could be reached by sea, the King of Portugal, Dom Manoel, set about organising a new expedition to the fabulous spice kingdom.

On its way, this expedition could also explore the western coast of the Atlantic, which Portugal had secured for itself since the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494.

As we have seen, the controversy over the “discovery” of Brazil is not the central issue.

Intentionally or not, the discovery of Brazil made Portugal a power. We should consider it a milestone in the great voyages of discovery, because it was the most powerful expedition ever organised by a European state.

We don’t know if the birth of Brazil was an accident, but there is no doubt that it was surrounded by great pomp.

The first ship to return from Vasco da Gama’s voyage arrived in Portugal in July 1499 to great excitement.

A few months later, on 9 March 1500, a fleet of 13 ships left Lisbon from the Tagus, the largest ever to leave the kingdom, apparently bound for the Indies, under the command of Pedro Álvares Cabral, a nobleman just over thirty years old.

After passing the Cape Verde Islands, the fleet headed west, away from the African coast, until it sighted what would become Brazil on 21 April.

On that date, there was only a short descent to land and it wasn’t until the following day that the fleet anchored off the coast of Bahia, in Porto Seguro (BUENO, 2007, p. 30).

The Atlantic crossing of Cabral’s fleet, from its departure from Lisbon to the sighting of land on the Brazilian coast, took about 44 days.

The voyage was marked by a number of incidents, the most serious of which was the loss of a ship that was never found. Despite this, the crossing was uneventful and confirmed the possibility of Brazil becoming a safe stopover and watering place for future expeditions to the Indies.

To understand a little more about daily life on board a caravel during the Atlantic crossing, we present a fragment from the “Golden Book of Brazilian History” by historians Mary Del Priore and Renato Pinto Venâncio (2001, pp. 14-17). Follow along below.

Despite being small – around 20 metres long – agile, able to zigzag against the wind and armed with heavy artillery, caravels were considered the best sailing ships on the high seas.

But even if the ship was good, everyday life on overseas voyages was far from easy.

The precariousness of hygiene on board began with the limited space available to passengers: about 50 centimetres per person.

On a ship with three decks, two were used for the cargo of the Crown, the merchants and the passengers themselves.

The third was usually used to store water, wine, timber and other useful items.

In the “castles” of the ships were the rooms of the officers – captain, master, pilot, overseer, clerk – and the sailors, where gunpowder, biscuits, candles, cloths, etc. were stored.

Bathing on board was impossible because, in addition to the lack of hygiene, drinking water was used for consumption and cooking food.

All sorts of parasites such as lice, fleas and bedbugs proliferated on bodies or in food. Confined to cabins, passengers would satisfy their physiological needs by vomiting or spitting next to those who ate their meals.

For this reason, a few litres of “lor water” were taken on board to disguise it. Between the constant stench and the natural rocking, seasickness was a constant problem.

To make matters worse, poor hygiene on board often contaminated the food and water on board.

Diarrhoea, for which there was no cure, quickly claimed those who were already dehydrated and malnourished.

Food on these long voyages was always a problem for the Portuguese Crown.

The usual food shortages in Portugal prevented the ships from being supplied with enough food.

The Royal Storehouse, which was responsible for supplying the ships, often simply failed to do so.

Chronic hunger and physical weakness contributed to the death of a significant number of sailors.

In Memória de um Soldado na Índia, Francisco Rodrigues Silveira complained that it was rare for “soldiers to escape from gum rot (the dreaded scurvy, a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C), fever, diarrhoea and other ailments…”.

As well as being scarce, the food on board was spoiled before the voyage even began.

Stored in damp holds, edible food rotted even faster during the voyage.

The ‘list of provisions’ usually included biscuits, salted meat, dried fish (mainly salted cod), lard, lentils, rice, broad beans, onions, garlic, salt, oil, vinegar, sugar, honey, sultanas, wheat, wine and water.

Not all passengers had access to these provisions, which were strictly controlled by a steward or the captain himself.

Senior officers would take the produce that was in the best condition and often sell it on a kind of black market to other hungry travellers.

Grumets and poor sailors were forced to consume “biscuits all rotten with cockroaches, and with very foul-smelling mould”, among other foods in an advanced state of decomposition.

Honey and sultanas were offered to the sick aristocratic crew.

The high fevers and delirium that afflicted many of the crew were the result of eating excessively salty and rotten meat, washed down with bad wine.

When there was a lull in the searing tropical heat, the hungry sailors would eat anything: shoe soles, leather from trunks, papers, biscuits full of insect larvae, rats, dead animals and even human flesh.

They quenched their thirst with their own urine.

But many preferred suicide to dying of thirst.

In reality, the dramatic situation of the sailors wasn’t much different from that of the peasants on land.

A labourer who dug from sunrise to sunset, seven days a week, earned no more than two pennies a day.

That was barely enough to buy a bushel of bread.

What about the livelihoods of whole families without food or clothing?

Many poor peasants preferred to escape hunger by risking the sea, even though they were aware of the hardships they would face on the way to India.

The dream of the spice empire was an encouragement and a possibility in a context of misery and hopelessness.

In this text we can see that the voyage was not comfortable at all, there was a shortage of practically everything, but many people preferred to face the hardships of the voyage than to stay on land and live a miserable life as peasants.

Scurvy – was a common disease among sailors travelling by sea to the Indies or the New World. This ‘illness’ was caused by a lack of vitamin C due to the poor diet on board.

The text also tells us what daily life was like on a caravel, and this reality lasted practically until the 19th century, when citrus fruits were added to the sailors’ diet, providing the vitamin, since the main cause of scurvy was precisely the lack of this vitamin.

With the consumption of fruit, the incidence of scurvy decreased considerably.

It is important to understand that Brazil did not initially become an important trading post for the Portuguese, because at that time it was important to consolidate trade relations with India. This was an arduous task, given that Portugal was a country with scarce human resources.

Pedro Álvares Cabral followed Vasco da Gama’s route and, either by accident or on purpose (it is conceivable that the Portuguese had information about the presence of land nearby), found the Brazilian coast and docked at Porto Seguro in 1500.

From there, the Portuguese set sail for India with 11 ships (one had broken up in the Atlantic and was never found, and a second was sent to Portugal with the news of the discovery of Brazil).

Despite the loss of four ships on the Atlantic crossing (one of them commanded by Bartolomeu Dias, the first man to circumnavigate Africa), Pedro Álvares Cabral arrived in Calicut with rich gifts for the Hindu Samorin, who had complained that Vasco da Gama had not given him a proper present.

The Muslim merchants who dominated trade in the region tried to prevent the Portuguese from getting the goods they wanted, and when Pedro Álvares Cabral captured a Muslim ship carrying spices, the merchants protested by attacking their trading post and killing those inside.

Pedro Ávares Cabral responded by capturing ten more Muslim ships and setting sail for Cochin and Cananor, where he finished loading his ships.

He returned to Lisbon in July 1501; the cargo of the six ships he had brought to port more than covered the cost of the expedition (MIGLIACCI, 1997, p. 46).

Pedro Álvares Cabral’s expedition was a success in every respect, taking possession of Brazil and establishing a solid base for trade with India.

In the next section we will examine the process of conquering Brazil after the ‘discovery’.

3. The conquest of Brazil

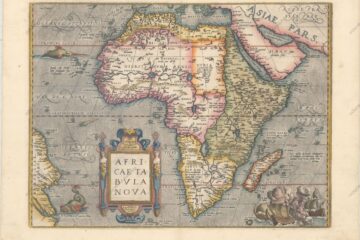

When the Portuguese officially “discovered” Brazil on 22 April 1500, it was inhabited by a large number of peoples spread over almost the entire territory of present-day Brazil. We can divide these Indian peoples into two main groups: the Tupis-Guaranis and the Tapuias.

The first group, called the Tupis-Guaranis, inhabited practically the entire Brazilian coast, from Ceará to Lagoa dos Patos, in present-day Rio Grande do Sul.

According to Boris Fausto (2007, p. 37):

The Tupis, also called Tupinambás, dominated the coastal strip from the north to Ananeia, in the south of what is now the state of São Paulo; the Guaranis were located in the Paraná-Paraguay basin and on the coastal strip between Cananeia and the extreme south of what would become Brazil.

Despite the different geographical location of the Tupis and Guaranis, we speak together as Tupi-Guarani because of the similarity of culture and language.

“These populations were called Tapuias, a generic word used by the Tupis-Guaranis to refer to Indians who spoke another language” (FAUSTO, 2007, p. 38).

The Tupis-Guaranis were more numerous than the Tapuias, but the Tapuias were fiercer than the former.

Both groups are of great importance in the context of pre-Columbian Brazil, as they developed unique cultural experiences in the prehistory of the American continent.

The classification mentioned in the previous paragraphs is based on contemporary anthropological studies, which have attempted to organise Brazil’s indigenous peoples according to their cultural affinities and language.

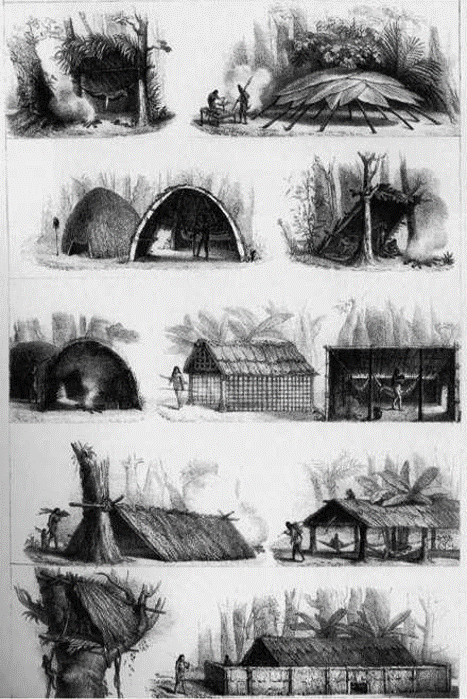

Both groups hunted, fished, gathered fruits and roots and farmed. Their experience in mastering nature would be put to good use by the Portuguese in the future process of colonising Brazil.

According to Boris Fausto (2007, p. 38), “[…] calculations vary between figures as different as 2 million for the entire territory and around 5 million for the Brazilian Amazon alone”. It is therefore difficult to determine the number of indigenous people at the time of ‘discovery’. This issue will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

To deepen the study of Brazil’s indigenous peoples, we will present a fragment from the book “História do Brasil: um olhar crítico” by the historian Gilberto Cotrim (1999, pp. 13-15), which deals with the Tupi culture.

The following are the basic characteristics of Tupi societies.

This characterisation is based on the records left by European missionaries and travellers in the 16th and 17th centuries.

However, despite the apparent similarity, any attempt to ethnographically synthesise these peoples is problematic because of the diversity of the societies that make up the Tupi linguistic family.

In order to describe the cultural diversity of the indigenous societies, the Europeans reduced them to two generic categories: Tupi-Guarani and Tapuia.

The Tapuia were groups little known to Europeans and perceived as the antithesis of Tupi and Guarani societies, i.e. groups that spoke languages other than Tupi and Guarani (Jês, Aruaques, etc.).

The Tupi-Guarani practised subsistence agriculture, the aim of which was to produce food to meet the survival needs of the group. There was no concern with accumulating surpluses.

They grew cassava, maize, sweet potatoes, beans, peanuts, tobacco, pumpkin, cotton, chillies, pineapple, papaya, yerba mate, guarana and many other plants. To prepare the land, the men cleared the forest, chopping down trees with stone axes and clearing the land by burning. The women did the planting.

Although they were farmers, the Tupi Guarani did not form fixed, permanent settlements: spatial mobility was still a cultural characteristic of these peoples. There were many reasons for a village to be relocated: wear and tear on the land, dwindling game reserves, factional disputes or the death of a chief.

The identity of each village was linked to the community leader, who was responsible for mobilising relatives and followers and organising material life. However, indigenous leadership generally did not confer economic or social privileges.

Despite a certain linguistic and cultural unity, the Tupi-Guarani Indians did not form a single society. On the contrary, they often formed rival groups, known by different names such as Tupinambás, Tupiniquins, Guaranis, Caetés, Potiguares, etc.

The Tupi-Guarani lived in a state of permanent war against their enemies, whether they were tribes from their own cultural matrix or tribes from other matrices, such as the Jês, the Aruaques, etc. The Tupi-Guarani lived in a state of permanent war against their enemies.

War, captivity and the sacrifice of captives were one of the foundations of relations between Tupi-Guarani villages in pre-colonial Brazil.

They were fundamental elements in intertribal relations and later in Euro-Indian relations. Understanding this dynamic of conflict provided the Europeans with one of the keys to controlling the indigenous population.

In countless areas of the country’s cultural expression (music, visual arts, literature, dance, religion, work techniques, etc.), we find the marked presence of indigenous societies.

Let’s take a look at some examples that illustrate this cultural presence in everyday Brazilian life:

- Food: potatoes, corn, cassava, sweet potatoes, bee honey, tomatoes, beans, peanuts, pineapples, papaya, guava, jabuticaba, passion fruit.

- Plants used in the world economy: rubber, cocoa, heart of palm, tobacco, yerba mate.

- Medicinal plants: jaborandi, copaiba, quinine, coca leaf,

- Industrial plants: cotton, piaçaba (broom), babaçu (oil).

- Vocabulary: Curitiba, Piauí, cashew, cassava, alligator, sabiá, tietê, armadillo, pineapple, and many others.

- Techniques: ceramic work, preparation of manioc and corn flour

It is important to stress that the contact with the Portuguese was a real catastrophe for the daily life of the native population.

The conquerors introduced new habits and customs, as well as a new religion that would later become dominant among the indigenous population.

Christianity was to be one of the main flagships of the Portuguese, with the Jesuits as its main representatives.

In the next section we will take a closer look at the Portuguese conquest of Brazil and its consequences for the indigenous peoples.

4. The arrival of the Portuguese in Brazil

We must understand that the process of colonisation and settlement in Brazil was not a “fairy tale”, but rather a painful historical process, especially for the indigenous peoples, a process full of ruptures.

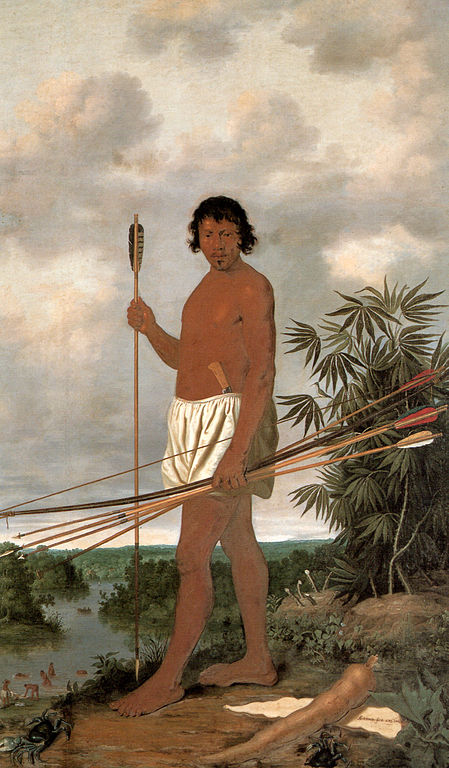

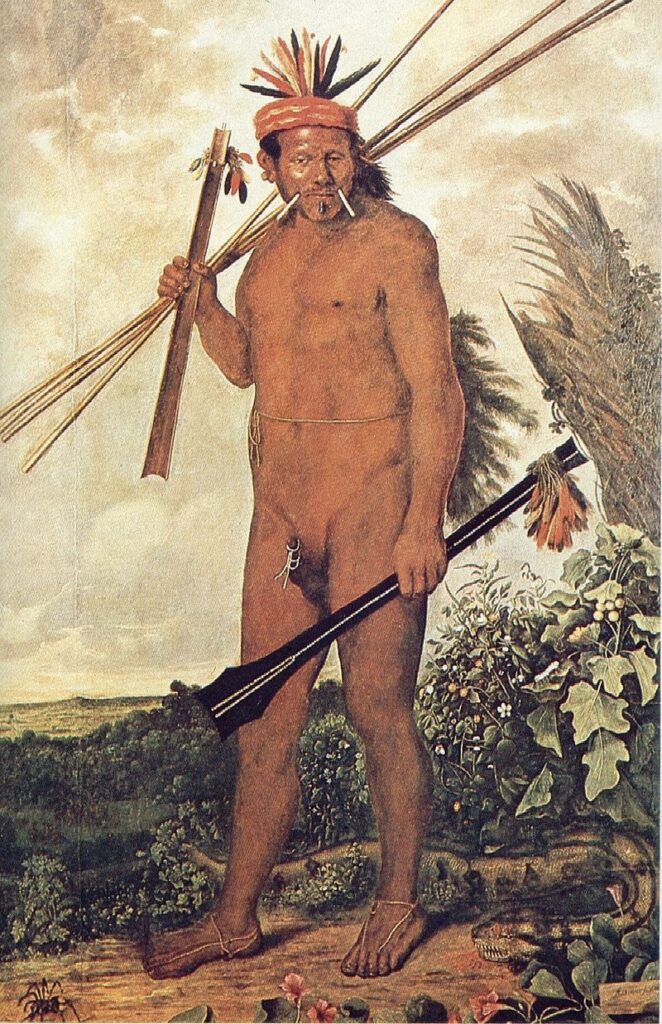

In his famous letter to the King of Portugal, Pero Vaz de Caminha (2002, p. 94), the scribe of Cabral’s squadron, reports that the inhabitants of the “newly discovered” lands had the following characteristics

Their characteristic is that they are brown, reddish, with good faces and noses, well made.

They walk around naked, without any covering.

They don’t bother to cover themselves or show their shame, and in that they are as innocent as when they show their faces.

Both of them had their lower lips pierced and their white, real bones stuck into them, the length of a hand, the thickness of a cotton thread, sharp at the end like an awl.

They put them in through the side of their cheeks, and the part between their cheeks and their teeth is made like a chequerboard, fitted so that it doesn’t bother or hinder them when they speak, eat or drink.

Their hair is flowing. And they were shorn, with a high shear, of good thickness, and shaved to just above the ears.

And one of them had a headdress of yellow bird feathers, about the length of a stump, very long and very serrated, which covered his head and ears.

And it was attached to the hair, feather and feather, with a soft paste like wax (but it wasn’t), so that the headdress was very round and very long and very even, and it didn’t need any more washing to lift it.

In his account, Caminha only describes the Indians, he doesn’t mention any conflict between Europeans and natives. We know that the first years of colonisation were relatively peaceful, but conflicts were not long in coming.

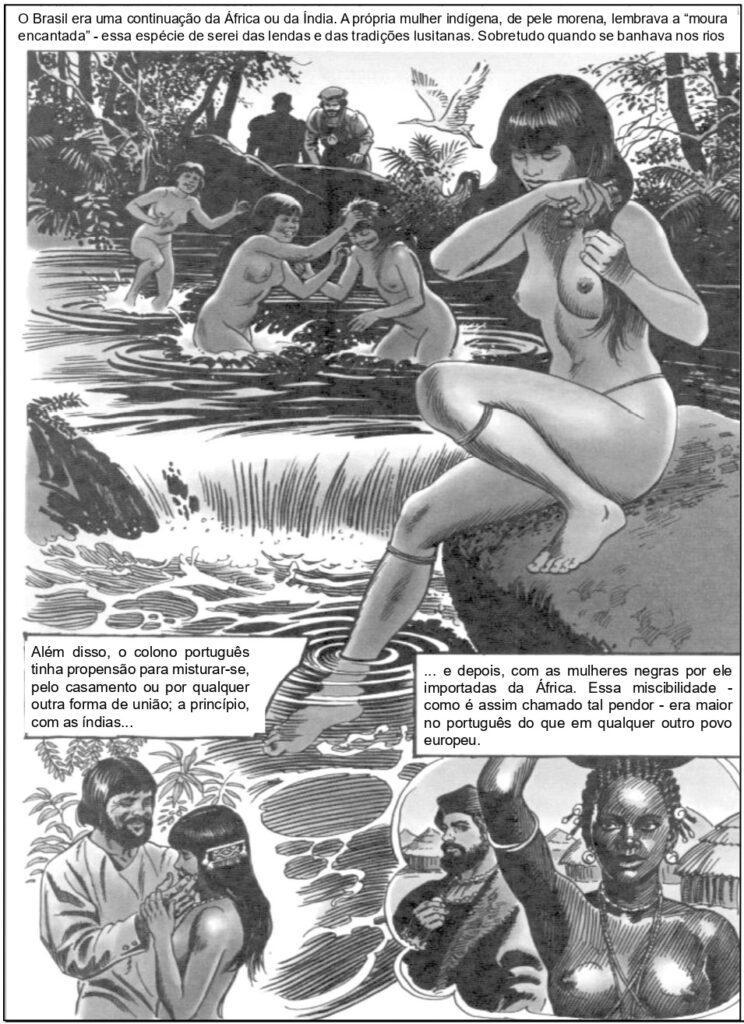

Gilberto Freyre states that when the Portuguese landed in Brazil, they found a native population still living in prehistoric times, with simple habits and a strong connection to nature.

Freyre creates a very interesting discussion by comparing the natives with the newly arrived Portuguese colonists.

The historian analyses the encounter between the natives and the colonisers, saying that the former were still in the adolescent phase of civilisation, while the Portuguese were already in the adult phase.

It is not, therefore, the meeting of an exuberant mature culture with another that is already adolescent; European colonisation surprises in this part of the Americas almost like a herd of large children; a green and incipient culture; still in its first teething stages; without the bones, the development or the resistance of the great American semi-civilisations (FREYRE, 2003, p. 158).

The first contacts were therefore peaceful and well understood. Nevertheless, the Portuguese always developed an arrogant attitude, indicating that their culture and religion were superior to those of the natives.

According to Mary Del Priore and Renato Pinto Venâncio (2001, p. 30):

Initially, the Portuguese did not interfere with the lives of the indigenous peoples and the autonomy of the tribal system.

Confined to three or four trading posts scattered along the coast, they depended on their “allies” for food and protection.

The exchange of products such as brazilwood, flour, parrots and slaves – the victims of wars between the tribes – for hoes, knives, scythes, mirrors and trinkets gave regularity to the arrangements.

But from about 1534, these relationships began to change.

If the whites had previously been submissive to the will of the natives, the panorama began to change. European ways of life and social institutions, such as the regime of the donatárias, began to take root in the new country.

In relation to the indigenous population, the colonisers’ initial idea was one of sympathy.

According to Nelson Werneck Sodré (1976, p. 56), the first contacts were “[…] simple, cordial, without obstacles or worries, from one side to the other, everything went smoothly, and there began to be unbridled praise, continuous praise, a curious repetition of qualities”.

An interesting cultural aspect that was part of colonisation, first with the alienation and then with the effective participation of the Portuguese, is directly related to the sexuality of both the coloniser and the native.

As Gilberto Freyre tells us:

The Europeans would jump ashore and slip on naked Indian women; the priests of the Company themselves had to descend carefully, lest they get their feet stuck in flesh.

Many of the other clergymen were contaminated by the debauchery.

The women were the first to give themselves to the whites, the most ardent rubbing themselves against the legs of those they thought were gods.

They would give themselves to the European for a comb or a piece of mirror (FREYRE, 2003, p. 161).

The following is an adaptation of the book “Casa Grande e Senzala” by the historian Gilberto Freyre (2001, p. 2), which shows, in cartoon form, a little of the history of the cultural relationship between the Portuguese and the natives.

The colonising Portuguese exerted a real fascination over the natives because of their technological superiority. In this context, Europeans and Indians coexisted peacefully during the first decades of the colonisation of Brazil.

Nevertheless, the process of conquest undertaken by the Portuguese would intensify when the decision was made to begin the process of colonisation itself.

This began in 1530 with the arrival of Martim Afonso de Sousa’s expedition.

It was natural that relations between Indians and whites were more harmonious in the early years of colonisation, because, in the words of Nelson Werneck Sodré (1976, p. 57)

In the early period of Brazilian life, when the coast was only patrolled or a few trading posts were established on it, there was no reason for friction between indigenous and new settlers.

They didn’t come to dispute the land, to appropriate it, to plant and harvest.

They were few in number, uninterested in the things of the new land, turned towards the ocean, hoping that on their return they would find, if not freedom, at least services, the resumption of contact with people who were their equals, who spoke their language and understood their aspirations.

The white man from the factories adapted to the life of the Indians, drew on his experience, lived with the Indians.

With the intensification of the colonisation and conquest process, this reality tended to change, as the Portuguese began to see the Indians as a labour force to be enslaved, and they also began to covet the lands occupied by the indigenous population.

These aspects tended to strain relations between the Indians and the Portuguese, leading to serious conflicts.

In the words of Sodré (1976, pp. 57-58)

In a second phase, when the settlers were definitively established, when it was strictly a question of colonisation – which did not happen all along the coast and at all times – relations were subverted.

The Indian was presented as a labour force, and a labour force with immense and irreplaceable advantages.

Then, as was inevitable, the struggle opened up and took on the proportions of systematic destruction.

With the introduction of monoculture, the process of conquering the indigenous peoples and the land itself took on unprecedented proportions. The consequences of this process would be the extermination of the tribes; the indigenous culture would not be able to support the production structure that was being established.

By replacing barter with agriculture, the Portuguese began to turn the tables.

The natives became both the main obstacle to the occupation of the land and the labour force needed to colonise it.

Subjugation, enslavement and trade became the main concern (DEL PRIORE; VENÂNCIO, 2001, p. 31).

The indigenous coastal populations were forced to migrate inland, losing a significant part of their population. Thus began the martyrdom of the Brazilian Indian, who went from ally to enemy in the space of a few decades.

The coastal Indians were forced to migrate inland, losing a significant part of their population. Thus began the martyrdom of the Brazilian Indians, who went from allies to enemies in just a few decades.

4. In this chapter we have seen that:

- Pedro Álvares Cabral’s expedition not only made the “discovery” of Brazil official, it also laid a solid foundation for trade with the East.

- The discovery of Brazil was either accidental or deliberate.

- Brazil was conquered, not discovered, because there were already people living there who were very different from the Portuguese.

- At first, relations with the natives were relatively peaceful, but this was to change as the process of settlement and colonisation intensified.

See the following periods in the history of colonial Brazil:

- Brazilian Independence – Breakdown of colonial ties in Brazil

- Portuguese Empire in Brazil – Portuguese royal family in Brazil

- Transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil

- Foundation of the city of São Paulo and the Bandeirantes

- Transition from colonial to imperial Brazil

- Colonial sugar mills in Brazil

- Monoculture, slave labour and latifundia in colonial Brazil

- The establishment of the General Government in Brazil and the founding of Salvador

- Portuguese maritime expansion and the conquest of Brazil

- Occupation of the African coast, the Atlantic islands and the voyage of Vasco da Gama

- Pedro Álvares Cabral’s expedition and the conquest of Brazil

- Pre-colonial Brazil – The forgotten years

- Establishment of the Portuguese Colony in Brazil

- Periods in the history of colonial Brazil

- Historical periods of Brazil

Publicações Relacionadas

The occupation of the African coast and Vasco da Gama's expedition

Independence of Brazil - breaking of colonial ties in Brazil

Foundation of the city of São Paulo and the Bandeirantes

History of the Fortresses and Defences of Salvador de Bahia

The history of sugar cane in the colonisation of Brazil

Monoculture, Slave Labour and Latifundia in Colonial Brazil

Transition between colonial and imperial Brazil

Establishment of the Portuguese colony in Brazil

History of the Captaincy of Todos os Santos Bay between 1500 and 1697

Carlos Julião: The Military Engineer and Draughtsman Who Portrayed Colonial Brazil

The Origin of Sugarcane and Sugar Mills in Colonial Brazil

Learn about the periods of Brazil's colonial history

Pre-colonial Brazil - The forgotten years

History of the sugar mills of Pernambuco - Beginning and end

Shipwreck of the Galeão Sacramento in Salvador: Learn the story

The History of the Jews in Colonial Brazil

Portuguese Empire in Brazil - Portuguese Royal Family in Brazil

Sugar Mills in Colonial Brazil: A Historical Insight

This post is also on:

![]() Português

Português ![]() English

English ![]() Deutsch

Deutsch ![]() Español

Español ![]() Français

Français